Pilgrims on a Popcorn Strewn Path

St. Ignatius of Loyola – who founded the Jesuits in the 16th century – had the insight that we all live in imagined worlds, and that our imagination constructs the worlds in which we live, using our experiences, our lived contexts, our hopes, our pains and our joys.

St. Ignatius of Loyola – who founded the Jesuits in the 16th century – had the insight that we all live in imagined worlds, and that our imagination constructs the worlds in which we live, using our experiences, our lived contexts, our hopes, our pains and our joys.

In effect we live in a highly selective world, and this world defines what is possible for us. It also defines how we see ourselves, how we interact with others and the context in which we find ourselves.

Today the media – particularly film and television – are powerful influences on our imagination. It is film and television which propose to us forms of the world and ways in which we might behave in those forms.

When we watch movies and TV shows we are more than being entertained; we are being formed and shaped. We expose ourselves to narratives that shape what is possible, and then we can – consciously or unconsciously – live out of those possibilities.

When we watch movies and TV shows we are more than being entertained; we are being formed and shaped. We expose ourselves to narratives that shape what is possible, and then we can – consciously or unconsciously – live out of those possibilities.

As early as 1920’s, the Church recognized that it wasn’t just the Church, the family and the school that were passing on values to children – the media had been added to the mix. To its credit, the Catholic Church – instead of succumbing to the temptation to attach the media – began a serious promotion of media education – giving our children the critical thinking tools they need to live in our mass mediated world. The Australian Bishops as far back as 1972 were calling this an “awesome responsibility before God and history.”

It’s a key concept of media education that we bring more than just our eyes and ears to the media we consume – we bring our complete selves. Each of us finds or “negotiates” meaning according to individual factors: personal needs and anxieties, the pleasures or troubles of the day, racial and sexual attitudes, family and cultural background, moral standpoint, and so forth.

Surprisingly, in learning to “read” – to be literate about – TV and movies, we have uncovered a trend towards spirituality in a place where we might not have expected to find it – the media. And yet there it is – clothed in the trappings of popular culture.

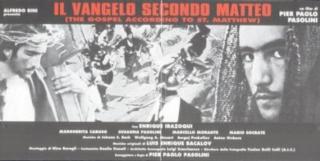

Hollywood’s preoccupation with the spiritual is not exactly new. It began with a segment in D.W. Griffith’s silent film classic Intolerance (1916) and continued through Hollywood epics in the 1960’s – The Greatest Story Ever Told and King of Kings. There have been two at least two musicals about Christ – Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell – both released in 1973 as well as the two so-called scandal films – The Life of Brian (1979) and The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). But, possibly, the finest and the most valid of the films about Christ was made by Pasolini in 1966 – The Gospel According to Saint Matthew.

The Christ story doesn’t get old with the telling – it’s as newsworthy today as it was 2,000 years ago. In 2004, The Gospel of John – a word by word filmed version of the Gospel – which found favour with Christian groups has both been denounced by some as a “pop-up” book and praised by others as an accurate and compelling portrayal of Christ.

Mel Gibson’s controversial movie, The Passion of The Christ (2004) , is based on the four Gospels, the writings of a 19th century German nun, Sr. Anne Catherine Emmerich, and other sources. Gibson has said that he did not try to make a religious movie but rather something that was real to him. He wanted the movie to be a contemplation in a spiritual way of the last hours of Christ.

Why do we go to the movies? We want to be entertained, to be distracted, to be informed, we have a thing for one of the stars, we like the particular genre, it’s a social outing, the issues and topics attract us, we are curious, or if you are a movie reviewer – it’s an assignment. These are all fairly common reasons for heading off to the cinema. But when we look more closely, there’s something deeper going on, something suspiciously spiritual.

Why do we go to the movies? We want to be entertained, to be distracted, to be informed, we have a thing for one of the stars, we like the particular genre, it’s a social outing, the issues and topics attract us, we are curious, or if you are a movie reviewer – it’s an assignment. These are all fairly common reasons for heading off to the cinema. But when we look more closely, there’s something deeper going on, something suspiciously spiritual.

The desire to be entertained and distracted comes from the attempt to escape boredom, that entrapment within oneself. To be a fan of a star is to engage in a form of identification through idealisation that ritualises one’s own religious longings for self-awareness. Genre movies appeal to basic drives within us. Detective flicks call upon our innate desire for order; horror movies allow us to face the fears of unknown powers that can destroy us; love stories affirm the power of relationships to maintain and foster identity. And should we go to the movies just to be with friends, then we see the cinema as a place for celebrating community.

In fact, it’s not a stretch to suggest that we go to see movies whose issues and topics attract us or we are curious about because we are seekers – pop pilgrims. We are exercising, consciously or not, a religious sensibility, and that exercise engages us in the rituals of self- transcendence, or classic spiritual enlightenment.

In fact, it’s not a stretch to suggest that we go to see movies whose issues and topics attract us or we are curious about because we are seekers – pop pilgrims. We are exercising, consciously or not, a religious sensibility, and that exercise engages us in the rituals of self- transcendence, or classic spiritual enlightenment.

So, we find ourselves in the cinema. Literally, spiritually, and metaphorically. The architecture of the theatre is designed for a religious ceremony in such a way that we can be both individual and part of a community. We sit in a sacred space differentiated from our everyday world by its manipulation of space and time. At the movies, it is neither day nor night. We are plunged into darkness, divorced from time of day or season of year. It is its own time. What time occurs is determined by what plays out before our eyes.

differentiated from our everyday world by its manipulation of space and time. At the movies, it is neither day nor night. We are plunged into darkness, divorced from time of day or season of year. It is its own time. What time occurs is determined by what plays out before our eyes.

In a technological update of St. Ignatius’ imaginative reality-building, both the context and what we are there to see are designed to engage and focus all our senses in a deliberately selective manner. That engagement is not passive. When a bright light shines through a moving strip of film, static images are projected onto a screen and artfully superimposed to give the illusion of movement. The mind creatively transforms that illusion into a semblance of reality, and the individual takes on the critical task of deciding whether or not to accept the imagined as real.

So,  at the movies – and indeed on our TV screens – we begin that pilgrim journey into the unknown to discover that we are more than who or what we think we are. We observe and reflect upon the actions and choices of the characters that attract our attention, and on the worlds in which they find themselves. We also reflect upon the way those characters and worlds are presented to us.

at the movies – and indeed on our TV screens – we begin that pilgrim journey into the unknown to discover that we are more than who or what we think we are. We observe and reflect upon the actions and choices of the characters that attract our attention, and on the worlds in which they find themselves. We also reflect upon the way those characters and worlds are presented to us.

Out of the encounter with what we contemplate we fashion our lives and the contexts we live in. Such contemplation is more than media literacy; it is genuine spiritual literacy. It may be a minor miracle but such spiritual literacy grows out of the pop culture of this mass mediated world in which we live.

In a way, Bart Simpson is perfectly correct when he says to his father, Homer: “It’s just hard not to listen to TV – it’s spent so much more time raising us than you have.” Television and movies have spent a great deal of time raising us. And that might turn out to be, after all, a good thing.

Richard Grover

Posted at 12:53h, 18 DecemberThanks John.60 years of learning and teaching about the media. WOW! I would love to read/hear your analysis of social media/computers and what effect they are having on us and our culture….or are social media and computers merely an extension of movies and TV ? Disinformation seems to flood our culture today. Richard

Peter Bisson

Posted at 12:58h, 18 DecemberThank you John!

Johnston Smith

Posted at 18:09h, 18 DecemberBroad in scope and in depth of meaning…like a colossal blockbuster!

Gerry (Ged) Ayotte

Posted at 20:40h, 18 DecemberThank you, John. Always inspired and moved by your insights. Richard’s comment recalls an article where Fr. Nicolas was cited (speaking in Mexico City in 2010): “Understanding the how of meaningful participation in the new social media landscape is critical because it engages many of the concerns raised by Superior General Adolfo Nicolás, S.J., about the impact of new technologies and associated practices on education generally and the richly reflective practice that characterizes Jesuit approaches to education in particular. Fr. Nicolás argues that the substantial benefits offered by wide access to new technologies notwithstanding, they nonetheless contribute to what he sees as “the globalization of superficiality—superficiality of thought, vision, dreams, relationships, convictions.” “

Eric Jensen

Posted at 17:22h, 19 DecemberA very insightful piece of writing!

Bart Simpson not withstanding, I’m one of those who were raised by radio, not TV. See (or watch) Woody Allan’s film, “Radio Days.”