Kicking the Habit: Dialogues des Carmelites

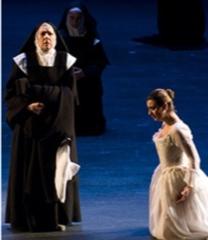

We had the luxury of seeing Dialogues des Carmelites at the Canadian Opera Company in Toronto, a few weeks ago. In the heart of one of the more secular cities in North America a dramatic and theological portrayal of prison discipleship and martyrdom was being rendered.  What was strikingly ironic was that the content, the vicarious sacrifice of the lives of these Carmelites nuns, was front and centre for a 21st century Western audience.

What was strikingly ironic was that the content, the vicarious sacrifice of the lives of these Carmelites nuns, was front and centre for a 21st century Western audience.

It’s not every day you see explicit Catholic themes of counter-cultural religious vows, the cost of a life of renunciation, non-violent resistance against a hostile secularism, and the self-surrender of life in martyrdom for the faith. Seen now in a radically different context and time, the symbols and gestures assume a new importance and reminder that the Christian life entails a conformity to the cross. Whoever seeks to bear the image of the resurrected Lord to the world, must first carry the cross.

The opera narrates the story of sixteen women, twelve of whom were cloistered nuns in a Carmelite monastery in Compiegne, France. They were accused of being a threat to the state during the Reign of Terror, imprisoned, and executed by the guillotine.

Their martyrdom in Paris on July 17th, 1794, inspired a novel by Van le Fort, a play by Bernanos, and an operatic score by Poulenc. The central character is Blanche de la Force (ably played by Isabel Bayrakdarian), a young French aristocrat who enters the Carmelite order as an escape from the growing political storm. Her journey of doubt and faith is echoed in her congregation who find themselves pawns in the hands of the French Revolution.

What was most remarkable in terms of staging is the lack of props and sets. Instead, they rely on a body of silent revolutionaries to create the atmosphere of approaching terror and threat. Credit goes to Cor van den Brink, lighting, in the use of an abstract, symbolic staging projected against looming walls that completely dominates the human figures. These elements highlight the human drama of the story, the life and death decisions, and the build up to the unavoidable end.

One can interpret the Dialogues through the standard Catholic lenses of the struggle between Church and State. This opposition is quite real in the opera. One witnesses the clash between Church and state and the state using violence in order to bring the Church to her knees. And one can interpret the dignified responses of the women as a heroic defiance of a small collective against a rampaging mob and the all-intrusive State. Such an interpretation is correct, but it would sadly leave Bernanos’ masterpiece at the level of social-political sphere.

Digging deeper, one sees in the Dialogues an exploration of the souls and hearts of persons who are facing oncoming persecution in and through their heart to heart conversations. The anguish of vulnerability and death of the nuns is not overcome by a heroism, but by a surrender of self into Divine providence and mercy. The women remind us that is in human weakness that the power of grace shines forth.

Digging deeper, one sees in the Dialogues an exploration of the souls and hearts of persons who are facing oncoming persecution in and through their heart to heart conversations. The anguish of vulnerability and death of the nuns is not overcome by a heroism, but by a surrender of self into Divine providence and mercy. The women remind us that is in human weakness that the power of grace shines forth.

The dimension of the ground where the Carmelite nuns find their strength is twofold. Firstly, consolation is found in unconditional obedience in God’s providence and mercy. Obedience is possible, because one hopes that God has won the final victory. What Bernanos adds to this is that the ground where the Carmelites, especially Blanche de la Force, rest their hope is not merely obedience in God, but also in a community.

Relevant here is the Catholic theological understanding of the Church as the living mystical Body of Christ. A person not only finds his or her consolation in obedience in God, he or she is called to incorporate himself or herself into a community that encompasses both earth and heaven—the communion of saints. In this community, men and women are able to pray for one another—to take the place of another, including sinners.  This notion that a mere person can substitute for another in order to aid the other’s salvation is not just present in Catholic piety, but also theology. The agonizing death of the Prioress implies a substitution in favor of the young Blanche.

This notion that a mere person can substitute for another in order to aid the other’s salvation is not just present in Catholic piety, but also theology. The agonizing death of the Prioress implies a substitution in favor of the young Blanche.

The words of Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger strike this point: “For the saints, hell is not a threat to be hurled at other people, but a challenge to oneself. It is a challenge to suffer in the dark night of faith to experience communion with God in His descent into the night. One draws nearer to the Lord’s radiance by sharing His darkness. One serves the salvation of the world by leaving one’s salvation behind for the sake of others.

The perils that beset humanity both in body, soul, individual, and community are not occasions for persons to evade, but an invitation to raise the bar of love in the face of hatred. In contemporary times, one think of Maximilian Kolbe who took the place of condemned person in Auschwitz. In the Dialogues of the Carmelites one sees something even more astonishing to the modern mind. There appears to be a substitution of destiny between the old dignified Prioress and the young and easily frightened Blanche de La Force.  The Prioress dies an agonizing and humiliating death instead of the sublime death that everyone expects. This death of the Prioress suggests a substitution she receives and undertakes in favor of the unsure and young Blanche. As one of the Carmelites—Sister Constance – hinted at the 3rd act of the opera, “We do not die for ourselves alone, but for one another, or sometimes even one in place of the other.”

The Prioress dies an agonizing and humiliating death instead of the sublime death that everyone expects. This death of the Prioress suggests a substitution she receives and undertakes in favor of the unsure and young Blanche. As one of the Carmelites—Sister Constance – hinted at the 3rd act of the opera, “We do not die for ourselves alone, but for one another, or sometimes even one in place of the other.”

As one moves the climax of the opera, one understands that the old Prioress takes on the death that the fearful young woman would have endured at the hands of the revolutionary mob. In the Prioress’ intercession, the young novice would face her death with unswerving grace and beauty. It is this mystical community, which encompasses living and the dead, that enables Blanche to remain faithful to her sisters and Carmelite vocation at the decisive moment when such fidelity really counts. As the audience witnesses the execution of the Carmelites, the nuns approach their Golgotha singing the Salve Regina and Veni Creator Spiritus.  As their voices are silenced one by one by the guillotine, the audience hears a childlike voice being added to the end. It’s a thin voice, but it holds no terror.

As their voices are silenced one by one by the guillotine, the audience hears a childlike voice being added to the end. It’s a thin voice, but it holds no terror.

The Canadian Opera Company enacted that story with intensity, pathos, and a beautiful minimalism. What was refreshing was its contemporary feel, moving beyond the borders of opera and into dramatic staging, lighting and choreography to create emotional impact. It was contemporary manifestation of love and life of grace. The symbolic nature of the production hints at much larger themes such as the meaning of love, the angst of suffering and the possibility of faith and hope.

The opera gradually builds itself into a haunting and heart-piercing conclusion, where tears were shed for the women who became the figure of the one who was crucified for humanity. The most haunting image is the final cruciform shapes of the white-robed fallen sisters, their bodies immobile but their dance still echoing. These sisters in Christ powerfully remind of the One who was crucified for us. Since theirs was a community that vowed fidelity to Christ, so theirs is a story that takes on the shape of Christ.

The opera gradually builds itself into a haunting and heart-piercing conclusion, where tears were shed for the women who became the figure of the one who was crucified for humanity. The most haunting image is the final cruciform shapes of the white-robed fallen sisters, their bodies immobile but their dance still echoing. These sisters in Christ powerfully remind of the One who was crucified for us. Since theirs was a community that vowed fidelity to Christ, so theirs is a story that takes on the shape of Christ.

No Comments