Duty, Dowager and Downton

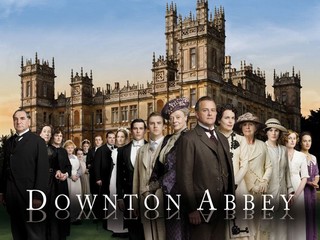

I don’t know about too many other Canadians, but I’ve been smitten with the television series, Downton Abbey. A period-piece if ever there was one, post Edwardian English society has been on colourful display. Of course, as one London critic observed, no one actually lived in quite that way.

I don’t know about too many other Canadians, but I’ve been smitten with the television series, Downton Abbey. A period-piece if ever there was one, post Edwardian English society has been on colourful display. Of course, as one London critic observed, no one actually lived in quite that way.

Yet it doesn’t matter. The series remained engrossing, and besides, if none lived as depicted, well, some nearly did. For me, I confess, the characters in Downton Abbey lived that way. Strewn about with fabulous “one-liners”, a layer of plots and sub plots intertwined throughout, and in time, entwined me.

Now with its third series ended, a fourth one is under way which will not air until January 2014. I can hardly wait.

Ever eager to allow an evening’s presentation to draw me in, I all but sat with a box of tissues by my elbow. Every possible emotion was wrung out, at least from me. The endless carrying on “downstairs”, love (straight, gay), flirtation, intrigue, quarrels, nastiness (O’Brien was especially given to that), stuffiness, whatever, relentlessly unfolded, with new intrigues, nastiness, love and scheming revealed whenever earlier ones disappeared. It’s all there and more besides.

Ever-present “duty” reigned “downstairs”, however wobbly at times, or better still, “responsibility” had to reign, as the perfect butler and master of all things below, Mr. Carson, trumpeted in his droning deep baritone voice.

However chastened by him, the young bucks seemed immune to his thundering, and continued to flirt tirelessly with the kitchen maids, and notably with Daisy. It was all to Carson’s displeasure. He is surely among the stodgiest and most unflinching of Victorian butlers one can imagine. Not even the gentle and endearing house-keeper, Mrs Hughes, could convince him that the Victorian age had passed.

Oh, and the sad tale of Mr John Bates! Or perhaps more aptly, “The Perils of Mr Bates”! Would it ever end! Tiresome melodrama it was, I found, and one waited longingly for his release from gaol so that this sub plot could be shut down. It did give, though, a hint of the viciousness in an English prison.

Oh, and the sad tale of Mr John Bates! Or perhaps more aptly, “The Perils of Mr Bates”! Would it ever end! Tiresome melodrama it was, I found, and one waited longingly for his release from gaol so that this sub plot could be shut down. It did give, though, a hint of the viciousness in an English prison.

“Upstairs”, the idle rich carried on their hollow lives. Only Matthew Crawley, his mother, the busy Isobel Crawley, and the remarkable over-painted New Yorker, Martha Levinson, seemed to possess any purpose in life.

Yet after all, they were middle class, as the Earl of Grantham archly pointed out, and would one expect otherwise. Perhaps the earl should have taken a leaf from the class he looked down on. Downton Abbey was saved once by the wealth of his American wife, Cora, but again nearly went under due to mismanagement and apathetic administration of his estate. It had to be rescued by Matthew, the personification of the middle class.

A friend in Montreal neatly summarized things on the telephone as we re-hashed the previous evening’s show: “The women seem to spend all their time re-arranging their hair and changing their gowns”. “Quite so! What else ought we do?” Violet, the Dowager Countess of Grantham no doubt would murmur, as only Maggie Smith could with that sideways “look” which is such a part of her acting.

The men, too, remained equally indolent, and mainly passed their time dressed or getting dressed in morning or evening attire, smoking cigarettes or large cigars while drinking cognac or whiskey. Or they sat bolt up-right behind glamorous English oak desks looking busy. They were not.

Work was not in the vocabulary of aristocratic English families, a point unwittingly acknowledged by the dowager countess when Matthew answered the question, “What do you do?” His response that he worked in an office produced one of the most extraordinarily amusing lines in the whole series. “Work?” asked the dowager countess, as her head swivelled around in near alarm, “What is that?” Indeed, a penetrating question from the idle rich!

A left-over relic from the Victorian age, she was oblivious to change or at most, puzzled if not alarmed by it. Who could blame her? She represented an age prior to the Great War when England believed it had achieved the perfect society. There was no need of anything further.

The Great War, which took up so much of the early series of Downton Abbey, destroyed all that. Yet the dowager countess and her class were slow to recognize this. She embodied tradition, proper behaviour and good manners of a by-gone era.

Of course there is nothing wrong with any of these. Rather it is when they ossify a whole society that they lose their essential worth. In an odd way, though, she also represented a kind of wisdom of age. The fact that so many, including the young Mr Crawley, sought her advice throughout, indicated that stability and tradition in the midst of change may be what we humans yearn for more than we know or want to admit.

The younger “set” in the family appeared to understand that, or at least somewhat. Edith and Sybil knew their lives should change. Yet how? That was the question. Ever ambiguous, yet in rather a dizzying manner that even Matthew found difficult to comprehend, Mary moved between her desire for change and her respect for tradition. She was not alone.

Although it came as a powerful shock, the sudden death of Sybil brought some taste of reality to the family. No matter how one reacted to anything else in the series, surely her death had to be among the most dramatic of scenarios.

Even Matthew’s surprise death later in a car accident, heart-breaking unquestionably, still did not carry the emotional intensity of Sybil’s. The near disintegration of her parent’s marriage as a result, and the crusty old dowager countess’ genuinely stunned and deeply distressed reaction at her young granddaughter’s death, heightened the disturbing effects some deaths can leave on a family, rich or less so. In fact, so emotionally charged was her death-scene and its aftermath, I was left telling myself that, after all, it is only fiction!

Indeed, everything else in the series seemed to pale in consequence. Notably the earl’s ranting and bigoted shouting over his motherless grandchild being baptized a Catholic seemed silly–however common such bigotry was at the time–and emotionally insipid. Likewise, the hostile anti-Catholicism of the local Anglican parson only came across, even to the younger ones at table, as offensive and mean-minded. In the face of that, one has all the more admiration and sympathy with the grieving Irish father, Tom Branson.

Stoic dignity in the face of unimaginable grief is not reserved to the rich alone, something that the earl, the parson and others had to learn if ever they could.

Well, thus the series unfolded. My Sunday evenings, crossed through with red ink for these past weeks, are free again. They’re already blocked out in red for next January. One knows Downton Abbey is fiction. Surely, though, one can day-dream. Or a little bit, no?

No Comments