The Life of Pi and The Quest For God

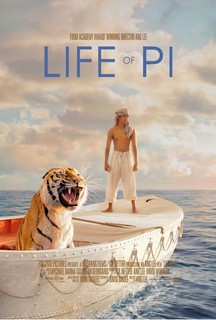

Insight into life’s deeper questions – suffering, the quest for God, and one’s place in the cosmos – are often handled more effectively in stories than in learned debates or arcane texts. A story of a young man adrift in a lifeboat with a man-eating tiger might be seen as an unlikely instrument for insight into these questions but the recent Ang Lee film The Life of Pi, based on the novel by Yann Martel, is filled with surprises and food for thought.

Insight into life’s deeper questions – suffering, the quest for God, and one’s place in the cosmos – are often handled more effectively in stories than in learned debates or arcane texts. A story of a young man adrift in a lifeboat with a man-eating tiger might be seen as an unlikely instrument for insight into these questions but the recent Ang Lee film The Life of Pi, based on the novel by Yann Martel, is filled with surprises and food for thought.

The story is a parable of humanity’s quest for the divine and transcendent in a world in which that presence seems to be hidden. The main character is a sort of modern day Job and the film version of the story has certain resonances with the interpretation of Job 38 in The Tree of Life.

The story begins in Montreal, as a Western writer looks up an Indian professor – Pi Patel – whose name he had been given by a friend. He had been assured that this man had an interesting story to tell, and since he was suffering from writers block, he was hoping for some inspiration. As they prepared dinner together, Pi related his life story.

Pi’s real name was Piscine Molitor Patel, after the famous Parisian Molitor swimming pool. Piscine became ‘Pissing’ to his schoolmates, so he shortened it to the mathematical symbol Pi to escape the merciless adolescent teasing.

Pi was a dreamer and a seeker, filled with curiosity, wonder, and a desire to learn. Much to his father’s dismay, who insisted that religion is darkness and that one must be modern and scientific, much of Pi’s searching was religious in nature.

He was attracted to Christianity and became a Catholic, but that did not stop him from practicing Islam and his native Hinduism. He was untroubled by boundaries and labels – somehow everything was reconciled deep within him. His only goal, he insisted, was to know and love God.

Economic troubles brought an end to his idyllic boyhood. His parents decided to emigrate to Canada along with their entire zoo. As the freighter carrying Pi, his family, and the entire zoological menagerie headed to Canada, it broke apart and sunk in a violent storm.

Pi found himself all alone in a life boat – not quite alone, but with a hyena, a zebra, a chimpanzee, and a man-eating Bengal tiger ludicrously named Richard Parker. Pi lost his entire family, but his afflictions were just beginning.

With the aid of the tiger, the zebra, hyena, and chimpanzee soon went the way of all flesh. Pi himself almost became the tiger’s lunch several times and he finally took to a small raft trailing behind the

boat.

Soon his meager supplies and the raft were swept away and he was forced to return to the boat, but as the days turned into weeks and months he and the tiger reached a wary and delicate coexistence. The tiger even became a sort of ‘friend’ or ‘companion’ for Pi, who carried on conversations with him reminiscent of Tom Hanks’ ‘friendship’ with the soccer ball named Wilson in Cast Away.

Pi’s reaction to events was illuminating and exceptional. He accepted the painful loss of his family and the setbacks and difficulties that followed as the hand of God. Indeed, every mini-disaster seemed to bring him even closer to God, and the occasional lifesaving fish or rainstorm he regarded as a divine gift.

There were truly beautiful scenes: a dark, nighttime ocean ablaze with luminescence; skies alive with stars and the moon; and a pod of huge whales that breached dangerously around the boat. Each of these was an epiphany for him – he seemed wild with delight and carried on a monologue of praise to the Creator.

Even the raging storm that threatened to drown him and the tiger was an occasion of exultant prayer. He stood in the boat amidst lightning and towering waves thanking God for everything and surrendering to the divine will. He was truly grateful for what most people would consider misfortune or disaster and truly saw the hand of God in everything.

Just when Pi and his friend Richard Parker were almost finished a small island mysteriously appeared that the narrator assured us is not found on any map. The strange little island had fresh water, fruit, and thousands of meerkats – real sustenance at last. There was a catch – at night the water turned poisonous and the terrified meerkats took to the trees, for the island itself became carnivorous.

With water and supplies replenished, Pi and the tiger returned to the boat, and after many months at sea washed up on the shore of Mexico. This is where the true loss began, for Pi was heartbroken to see Richard Parker, to whom he had become much attached, walk away and disappear in the jungle without once looking back.

Representatives from the Japanese shipping company came to question him in his hospital room. Since he was the sole survivor, they wanted to know what happened and why the ship sank. He narrated his story to them but they were incredulous and uneasy and asked how they could be expected to believe the tale. Admittedly, it was fantastic and almost tinged with magic.

After a moment’s thought he narrated another account: there were no animals, epiphanies, or miraculous events. He was in the lifeboat with his mother and two other crewman, one of whom was the coarse and venal cook. There was fighting, murder, and cannibalism.

The final act was Pi’s killing of the cook in revenge for the murder of Pi’s mother. He told them a tale they could relate to and perhaps what they expected but they still seemed unconvinced and finally left.

We return to the present, and an adult Pi finishes his account just as his wife and two children return. As he is introduced to the family, the writer can see that Pi’s life is joyful and fulfilled. He is still filled with God and even studies the Jewish Kabbalah at the University.

Before the writer leaves, he asks Pi the big question – the one that we probably also have – which of the two stories is true? Looking the writer straight in the eye, Pi gently but firmly urges him to choose the one he prefers. Thinking for a moment, the writer says, ‘I like the first one – it’s a better story!’ Pi replies, ‘And so it is with God.’

We are presented with many stories in today’s world. One of them insists that we are the result of blind, mechanistic forces, and that there is no God or purpose to the universe. Another story describes life as nasty, brutish, and short – the world is an ugly and mean place to live so watch your back and get them before they get you.

There are many variations and sub-stories, but many share to some degree in these two worldviews. But there is another story, told by people of many different traditions. Despite the painful and difficult elements of earthly life and the stupid and terrible things that people often do, the world is a beautiful place. To borrow Gerard Manley Hopkins’ phrase, the world is ‘charged with the grandeur of God.’

God is truly to be found in all things, even the painful or negative ones. We are all one with God, one another, and creation. Pi’s story brought him through experiences that might have killed others. It brought him happiness, joy, and peace. Now we must choose the story that speaks to us. Some will choose from the first two stories, but for so many, the story with God in it is definitely the better story.

No Comments