Copernicus and The Catholic Scientists

A ready observation of pop culture (I can think of two songs), popular science, and popular history, would indicate a widespread assumption that church authority has had a frought and acrimonious relationship with science (ask anyone about Galileo). The subtext seems to be that religion is threatened by science, and that religious authority clings irrationally to its “power” by attempting to suppress or refute scientific evidence. Yet, perhaps the tendency to see things in such adversarial terms (the sympathy always falling to science), is an expression of a certain need to make an “a priori” dismissal of religion’s own rich tradition of mediating spiritual, philosophical and scientific truths, which taken together are, by nature, existential and personal.

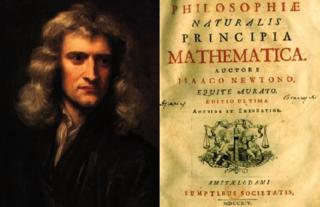

But a look at the rise of rationalism and scientific inquiry in the 17th century largely proves otherwise. The list of founding scientists and philosophers who were also convinced theists (some even priests, monks or churchmen), goes on and on: the Cambridge Platonists, Henry More, Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton — even John Locke remains convinced about the compatibility of faith and reason. The rationalism of this particular group of British thinkers was perhaps a bit reductive religiously (and the Deism that also arose seems to have exulted reason to such an extent that revelation was second place, and the Christ of Christianity all but dismissed). But in any case, one finds there was little opposition from Protestant religious authority to the new discoveries of scientific inquiry. This flies in the face of the “conventional wisdom”.

But a look at the rise of rationalism and scientific inquiry in the 17th century largely proves otherwise. The list of founding scientists and philosophers who were also convinced theists (some even priests, monks or churchmen), goes on and on: the Cambridge Platonists, Henry More, Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton — even John Locke remains convinced about the compatibility of faith and reason. The rationalism of this particular group of British thinkers was perhaps a bit reductive religiously (and the Deism that also arose seems to have exulted reason to such an extent that revelation was second place, and the Christ of Christianity all but dismissed). But in any case, one finds there was little opposition from Protestant religious authority to the new discoveries of scientific inquiry. This flies in the face of the “conventional wisdom”.

Where our modern history books, especially in the English-speaking world, seem to be incomplete, however, is on the scientific role played by Catholic scientists outside the Anglo sphere: in Poland, France and Italy. Indeed, there is sometimes an uneven jump from the early modern period, with its Renaissance genesis in Italy (Nicholas Cusanus, Da Vinci, etc.) and the Baroque period (Jesuit schools with their keen embrace of science and liberal arts) — to the rise of 17th century rationalism.

A much more ample account of the relationship of science and faith would consider the wider continental sources and developments. And of course it should do this without cherry-picking the Galileo trial outside of its proper context. It would acknowledge that whenever church authority had a quibble with the writings of these philosopher-scientists, it was usually just as much (if not more) on scientific grounds than on religious ones. Like all good historians, if we remove ourselves from the perspectives of the present, we recall there was less compartmentalization of science and theology, faith and reason.

Take Nicholaus Copernicus — the “founder” of modern astronomy, and purveyor of the heliocentric theory. Essentially a Dominican friar (3rd order) in Poland, he is educated there and in Italy. When his work “De revolutionibusorbium coelestium” advocated the then-revolutionary (and bizarre-sounding to all his contemporaries) theory that the earth is in orbit around the sun, a series of lectures on the idea was delivered in Rome, where Pope Clement VII and several cardinals were quite interested. The archbishop of Capua then wrote to Copernicus, urging him to make his theory known to wider scientific purview:

Take Nicholaus Copernicus — the “founder” of modern astronomy, and purveyor of the heliocentric theory. Essentially a Dominican friar (3rd order) in Poland, he is educated there and in Italy. When his work “De revolutionibusorbium coelestium” advocated the then-revolutionary (and bizarre-sounding to all his contemporaries) theory that the earth is in orbit around the sun, a series of lectures on the idea was delivered in Rome, where Pope Clement VII and several cardinals were quite interested. The archbishop of Capua then wrote to Copernicus, urging him to make his theory known to wider scientific purview:

“Some years ago word reached me concerning your proficiency, of which everybody constantly spoke. At that time I began to have a very high regard for you… For I had learned that you had not merely mastered the discoveries of the ancient astronomers uncommonly well but had also formulated a new cosmology. In it you maintain that the earth moves; that the sun occupies the lowest, and thus the central, place in the universe… Therefore with the utmost earnestness I entreat you, most learned sir, unless I inconvenience you, to communicate this discovery of yours to scholars, and at the earliest possible moment to send me your writings on the sphere of the universe together with the tables and whatever else you have that is relevant to this subject…”

The Church had always had an interest in astronomy, since holy days and the liturgical calendar were determined by astronomical data. The Gregorian calendar, which we still use today for our calendar year, was promulgated by Pope Gregory XIII on the basis of such research in 1582, and an observation tower built in 1580 for the same reason. The famed Vatican Observatory would be a successor. Its present director, the Jesuit Br. Guy Cosolmagno, spoke at Toronto's Newman Centre in February.

Indeed, it is illuminating to find that Copernicus’s later critics,e.g., Bartolomeo Spina and Giovani Tolosani opposed the heliocentric theory primary because it: a) contradicted their own astronomy (which was being used to adjust the calendar), and b) because they thought Copernicus’s theory was scientifically unproven and unfounded. According to Tolosani, Copernicus has assumed the earth moved but had offered no physical theory on which to base this. He thought Copernicus had come up with an idea and chosen phenomena that supported it, rather than the other way around. In order words, he was critical of Copernicus’s science on the basis of scientific criteria.

A much similar historical reading can be made of the Galileo case. While it is true that both science and scripture were cited as proofs contra (again, reason and faith were much more closely allied in appraisals), the beef against Galileo was that he considered heliocentrism a truth and not an opinion or theory. His primary debater was Francesco Ingoli, who wrote an essay containing eighteen mathematical and physical arguments against heliocentrism, borrowing mostly from Tycho Brahe, and only four theological arguments.

A much similar historical reading can be made of the Galileo case. While it is true that both science and scripture were cited as proofs contra (again, reason and faith were much more closely allied in appraisals), the beef against Galileo was that he considered heliocentrism a truth and not an opinion or theory. His primary debater was Francesco Ingoli, who wrote an essay containing eighteen mathematical and physical arguments against heliocentrism, borrowing mostly from Tycho Brahe, and only four theological arguments.

It didn’t help that Galileo isolated his then-advocate Pope Urban VIII by putting Urban’s words in the mouth of an aristotelean character called “Simplicius” or “Simpleton” in his book. Only when advances were made in the manufacturing of telescopes were the heliocentric theories verified scientifically.

What is interesting today is that modern astrophysics is starting to show that the philosophic-scientific geocentric approach is not necessarily wrong. Does the earth orbit the sun, or does the sun and the other planets orbit the earth? It depends on your "point of view". As there is no fixed reference point in space, in a sense, both are true.

Where, then, does this leave us? Despite the efforts of popular science and history, as well as the “scientism” of the new atheists, there is today a rapprochement between faith and science in the Catholic Church, a union never really lost. If we look beyond our English-speaking history books which have narrow perspectives on the relationship between Church and science, we will discover a rich and varied history. Are there other religious figures who pioneered advances in science? Are there scientists who had great religious ideas? The answer is yes, but that’s for others to write about.

Where, then, does this leave us? Despite the efforts of popular science and history, as well as the “scientism” of the new atheists, there is today a rapprochement between faith and science in the Catholic Church, a union never really lost. If we look beyond our English-speaking history books which have narrow perspectives on the relationship between Church and science, we will discover a rich and varied history. Are there other religious figures who pioneered advances in science? Are there scientists who had great religious ideas? The answer is yes, but that’s for others to write about.

No Comments