Getting to Know the Relations – (5)

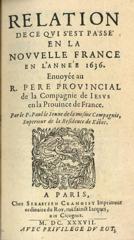

For more than 400 years, Jesuits working in Canada have written about their daily life and mission. Originally, their letters were published as The Jesuit Relations (Relations des jésuites). This blog, igNation, continues that tradition with a new series entitled: Getting to Know the Relations.

Using excerpts chosen from the first 200 hundred years of these documents, the series presents vignettes which speak to the timeless heart of Jesuit endeavour: the promotion of discernment in order to help people find God in all things.

These excerpts are found in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents – Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in North America (1610 – 1791), selected and edited by Edna Kenton, and published in 1954 by the Vanguard Press. That edition uses the word “savages” throughout. In these excerpts that word has been replaced by “the people who were here before we arrived” or “the people here.”)

Today: Something between a hovel and a palace

In 1635, Jean de Brébeuf writes about the mission’s real estate – a multipurpose cabin:

The cabins of this country are neither Louvres nor Palaces, nor anything like the buildings of our France, not even like the smallest cottages. They are, however, somewhat better and more commodious than the hovels of the Montagnais. I cannot better express the fashion of the Huron dwellings than to compare them to bowers or garden arbors, some of which, in place of branches and vegetation, are covered with cedar bark, some others with large pieces of ash, elm, fir, or spruce bark; and, although the cedar bark is best, according to common opinion and usage, there is, nevertheless, this inconvenience, that they are almost as susceptible to fire as matches. Hence arise many of the conflagrations of entire villages.

There are cabins or arbors of various sizes, some two brasses in length [a brass=1.8 metres], others of twenty, of thirty, of forty; the usual width is about four brasses, their height is about the same. There are no different storeys; there is no cellar, no chamber, no garret. It has neither window nor chimney, only a miserable hole in the top of the cabin, left to permit the smoke to escape. This is the way they built our cabin for us.

The people … of our village were employed at this by means of presents given them. It has cost us much exertion to secure its completion, we were almost into October before we were under cover. As to the interior, we have suited ourselves; so that, even if it does not amount to much, the [people who were here when we arrived] never weary of coming to see it, and seeing it, to admire it. We have divided it into three parts.

The first compartment, nearest the door, serves as an ante-chamber, as a storm door, and as a storeroom for our provisions, in the fashion of the [people here]. The second is that in which we live, and is our kitchen, our carpenter shop, our mill, or place for grinding wheat, our Refectory, our parlor and our bedroom. On both sides, in the fashion of the Hurons, are two benches which they call Endicha, on which are boxes to hold our clothes and other little conveniences; but below, in the place where the Hurons keep their wood, we have contrived some little bunks to sleep in, and to store away some of our clothing from thieving hands of the Hurons.

The first compartment, nearest the door, serves as an ante-chamber, as a storm door, and as a storeroom for our provisions, in the fashion of the [people here]. The second is that in which we live, and is our kitchen, our carpenter shop, our mill, or place for grinding wheat, our Refectory, our parlor and our bedroom. On both sides, in the fashion of the Hurons, are two benches which they call Endicha, on which are boxes to hold our clothes and other little conveniences; but below, in the place where the Hurons keep their wood, we have contrived some little bunks to sleep in, and to store away some of our clothing from thieving hands of the Hurons.

They sleep beside the fire, but still they and we have only the earth for bedstead; for mattress and pillows, some bark or boughs covered with a rush mat; for sheets and coverings, our clothes and some skins do duty.

The third part of our cabin is also divided into two parts by means of a bit of carpentry which gives it a fairly good appearance, and which is admired here for its novelty. In the one is our little Chapel, in which we celebrate every day holy Mass, and we retire there daily to pray to God. It is true that the almost continual noise they make usually hinders us, and compels us to go outside to say our prayers. In the other part we put our utensils. The whole cabin is only six brasses long, and about three and a half wide. That is how we are lodged, doubtless not so well that we may not have in this abode a good share of rain, snow and cold.

However, they never cease coming to visit us from admiration, especially since we have put on two doors, made by a carpenter, and since our mill and our clock have been set to work. It would be impossible to describe the astonishment of these good people, and how much they admire the intelligence of the French. No one has come who has not wished to turn the mill; nevertheless we have not used it much, inasmuch as we have learned that our sagamites [a paste of corn to which meat and fish can be added] are better pounded in a wooden mortar, in the fashion of the people here, than ground within the mill. I believe it is because the mill makes the flour too fine.

As to the clock, a thousand things are said of it. They all think it is some living thing, for they cannot imagine how it sounds of itself; and when it is going to strike, they look to see if we are all there, and if some one has not hidden, in order to shake it. They think it hears, especially when, for a joke, one of our Frenchmen calls out at the last stroke of the hammer, "That's enough," and then it immediately becomes silent.

They call it the Captain of the day. When it strikes they say it is speaking; and they ask when they come to see us how many times the Captain has already spoken. They ask us about its food; they remain a whole hour, and sometimes several, in order to be able to hear it speak. They used to ask at first what it said. We told them two things that they have remembered very well; one, that when it sounded four o'clock of the afternoon, during winter, it was saying, "Go out, go away that we may close the door," for immediately they arose, and went out. The other, that at midday it said, yo eiouahaoua, that is, "Come, put on the kettle;" and this speech is better remembered than the other, for some of these spongers never fail to come at that hour, to get a share of our Sagamite.

They eat at all hours, when they have the wherewithal, but usually they have only two meals a day, in the morning and in the evening; consequently they are very glad during the day to take a share with us.

Speaking of their expressions of admiration, I might here set down several on the subject of the loadstone, into which they looked to see if there was some paste; and of a glass with seven facets, which represented a single object many times, of a little phial in which a flea appears as large as a beetle; of the prism, of the joiner's tools; but above all, of the writing; for they could not conceive how, what one of us, being in the village, had said to them, and put down at the same time in writing, another, who meantime was in a house far away, could say readily on seeing the writing. I believe they have made a hundred trials of it.

All this serves to gain their affections, and to render them more docile when we introduce the admirable and incomprehensible mysteries of our Faith; for the belief they have in our intelligence and capacity causes them to accept without reply what we say to them.

(108-9)

No Comments