A Lenten Bookshelf: A Six-Fold Path: Week One – The Seven Storey Mountain

By the solemn forty days of Lent the Church unites herself each year to the mystery of Jesus in the desert.

(From Article 540 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church)

In this six-part series, Kevin Burns selects a book for each week of Lent. Each book speaks to one of the great traditions within Catholic culture. Each book also shows how its author integrates that tradition. Six different approaches to the same journey through the desert of Lent to the Easter promise of resurrection.

Week One: Thomas Merton encounters the severity of the Trappist Lent.

The Seven Storey Mountain has been in print since 1948. It made a young reclusive monastic, Thomas Merton, an international literary star. In many ways, this cautiously restrained book is the least characteristic of all the work he published in his lifetime. It does contain, however, that central element that makes all of his work so readable and memorable: his inexhaustible pursuit of the sacred within the day to day details of life.

The Seven Storey Mountain has been in print since 1948. It made a young reclusive monastic, Thomas Merton, an international literary star. In many ways, this cautiously restrained book is the least characteristic of all the work he published in his lifetime. It does contain, however, that central element that makes all of his work so readable and memorable: his inexhaustible pursuit of the sacred within the day to day details of life.

In this selection from close to the end of the book Merton describes his first Lent at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky. Newly arrived there, his idealistic thoughts about religious life are interrupted by the arrival of the first of two letters. His heightened experience of the liturgical season of Lent becomes inextricably linked with another death, that of his younger brother. Merton writes:

And so 1943 began, and the weeks hastened on towards Lent.

… I had fasted a little during my first Lent, the year before, but it had been broken up by nearly two weeks in the infirmary. This was my first chance to go through the whole fast without any mitigation. In those days, since I still had the world's ideas about food and nourishment and health, I thought the fast we have in Trappist monasteries in Lent was severe. We eat nothing until noon, when we get the regular two bowls, one of soup and the other of vegetables, and as much bread as we like, but then in the evening there is a light collation-a piece of bread and a dish of something like applesauce-two ounces of it. However, if I had entered a Cistercian monastery in the twelfth century-or even some Trappist monasteries of the nineteenth, for that matter-I would have had to tighten my belt and go hungry until four o'clock in the afternoon: and there was nothing besides that one meal: no collation, no frustulum.

Humiliated by this discovery, I find that the Lenten fast we now have does not bother me. However, it is true that now in the morning work periods I have a class in theology, instead of going out to break rocks on the back road, or split logs in the woodshed as we did in the novitiate. I expect it makes a big difference, because swinging a sledge-hammer when you have an empty stomach is apt to make your knees a little shaky after a while. At least that was what it did to me.

Merton endures these deprivations of Lent and has a joyous experience of Easter. Then the first of two letters arrives.

… it was Easter Tuesday, and we were in choir for the Conventual Mass, when Father Master came in and made me the sign for "Abbot." I went out to Reverend Father's room. There was no difficulty in guessing what it was.

I passed the pieta at the comer of the cloister, and buried my will and my natural affections and all the rest in the wounded side of the dead Christ.

Reverend Father flashed the sign to come in, and I knelt by his desk and received his blessing and kissed his ring and he read me the telegram that Sergeant J. P. Merton, my brother, had been reported missing in action on April 17th.

… Some more days went by, letters of confirmation came, and finally, after a few weeks, I learned that John Paul was definitely dead.

The story was simply this. On the night of Friday the sixteenth, which had been the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows, he and his crew had taken off in their bomber with Mannheim as their objective. I never discovered whether they crashed on the way out or the way home, but the plane came down in the North Sea. John Paul was severely injured in the crash, but he managed to keep himself afloat, and even tried to support the pilot, who, was already dead. His companions had managed to float their rubber dinghy and pulled him in.

He was very badly hurt: maybe his neck was broken. He lay in the bottom of the dinghy in delirium.

He was terribly thirsty. He kept asking for water. But they didn't have any. The water tank had broken in the crash, and the water was all gone.

It did not last too long. He had three hours of it, and then he died. Something of the three hours of the thirst of Christ Who loved him, and died for him many centuries ago, and had been offered again that very day, too, on many altars.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

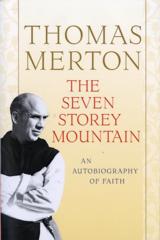

The Seven Story Mountain was published originally by Harcourt, Brace and Company in 1948. In 1998 the same publishers brought out a special 50th anniversary edition of the work and this is the edition that is currently available. (Photo courtesy of Harcourt Brace)

Next Week:

Judith Valente on the Benedictine path. “We say a prayer, promising to give ‘strength and support to one another on the Lenten journey to the Easter Triduum’.”

No Comments