The Terrible Father Quirk

Students at Loyola College in the early part of the twentieth century found Nicholas A. Quirk, S.J., somewhat eccentric. He was to some extent, yet not to the degree the stories from that era would suggest. Quirk was among the earliest teachers at Loyola College, having been assigned there in 1899.

Students at Loyola College in the early part of the twentieth century found Nicholas A. Quirk, S.J., somewhat eccentric. He was to some extent, yet not to the degree the stories from that era would suggest. Quirk was among the earliest teachers at Loyola College, having been assigned there in 1899.

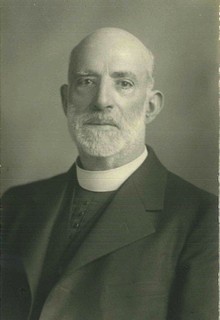

Ever sphinx-like, tall and strict looking, he rarely appeared without his long black outer garment, the cassock–which all Jesuits wore at the time–and his cincture firmly round his thin waist, neatly in place and at the proper position, not too high and not too low.

That was accompanied by a black biretta–again a necessary apparel of every Jesuit except a novice–placed firmly on his elongated head. The biretta seemed ready to topple at any time from its precarious perch. Yet it never did.

Nothing, and definitely no student, ever eluded his eagle-like gaze. As the Assistant or Sub Prefect of Discipline and, after 1912, as Prefect of Discipline, “the terrible Father Quirk”, as he was known, seemed always to be there when most students hoped that he would be elsewhere.

Boarding students who defied the rules to go off campus without permission were especially alert to his habit of appearing from nowhere at, for them, the wrong moment while they snuck into the building, usually through a basement window left open for such a purpose.

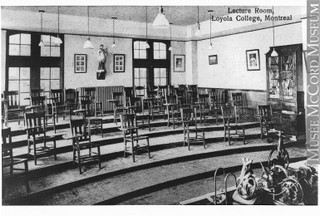

With “Black Book” in hand, and ominously motionless in a door-way, as one student described him, or more regularly standing under the clock in the corridor, he carefully scrutinized every student filing to class.

Conversation ceased as students approached him. They silently hoped to get past lest whatever misdemeanour was on their conscience would be revealed before all. In their minds, somehow he knew everything.

Quirk had been born in Brooklyn, New York, and never lost that accent. Indeed, students never forgot his strong nasal accent along with that one question he would ask any student who approached him: “What’s the matter now?”

Still, they seemed not to have questioned his fair-mindedness or doubted the impartiality of his punishments, “jug” being the most frequent penalty for misbehaviours.

Quirk was a born teacher, friendly enough in a reluctant sort of way, certainly caring, and eminently objective. Very knowledgeable in the Jesuits’ educational ideals expressed in their Ratio Studiorum, he was renowned in the way he applied those, aemulatio (rivalry, competition) and repetitio (repetition) being especially his forte.

For thirteen years at Loyola College he oversaw his ever attractive and well-disciplined classroom. His grammar and spelling competitions quickly became legendary. For those, he would split his class into “Romans and Carthaginians”. The ensuing competition had students clamouring to vie with each other.

Years later, in 1936, and now greatly mellowed yet nonetheless still firmly enigmatic with his “reputation” from his earlier time at Loyola still intact, Quirk returned there as spiritual counsellor. Shortly afterwards he fell gravely ill and retired. For years afterwards, he was still fondly remembered by the alumni of Loyola College.

No Comments