The first time I met Bill Clarke was back in 1998 when I was preparing a documentary for Tapestry on CBC Radio One. I spent a week at the Ignatian Farm in Guelph, Ontario. Tapestry’s then host, Marguerite MacDonald explained the focus of the piece in her introduction:

“One of the deepest longings we have is knowing that somewhere we belong. For people with mental or physical handicaps, finding a place to call home can be the most difficult challenge of all. Especially for those who were once looked after in institutions and who now find themselves in places that are not always welcoming. And some communities are just not welcoming. We’ve all heard news reports of ‘not in my back yard’ conflicts. Plans for halfway houses for former drug dependents, former prison inmates, people who are handicapped in some way, sometimes run into problems. People are made to feel unwelcome.

Just outside Guelph, about an hour west of Toronto, there is an experiment in community life where everyone is made to feel welcome. Founded over 20 years ago by a Jesuit priest, the Ignatian Farm Community continues to open its doors to needy people. Needy because of their mental, or physical and other challenges.”

To understand more of this “experiment in community life” I spent a week on the farm, recording interviews, sitting in on meetings, observing as much as I could, and trying not to get in the way. At the time, Bill Clarke was the director, a position he’d held for almost two decades. In the documentary I set up our initial meeting like this: “Bill Clarke told me at breakfast he’d be putting the finishing touches on the new hermitage he’s built. So that’s where I find him. A hermitage is a place for silent reflection. There’s a bed, a wood stove, a camping stove for cooking, and a place set aside for prayer. Anyone in the community can come to the hermitage on their day off. Bill Clark is a striking figure. He’s a short wiry man with a shock of white hair that is even more noticeable because of his dark brown skin. He tells me that he finds the experience of working the land – and living in a community like this – a form of contemplation.”

To understand more of this “experiment in community life” I spent a week on the farm, recording interviews, sitting in on meetings, observing as much as I could, and trying not to get in the way. At the time, Bill Clarke was the director, a position he’d held for almost two decades. In the documentary I set up our initial meeting like this: “Bill Clarke told me at breakfast he’d be putting the finishing touches on the new hermitage he’s built. So that’s where I find him. A hermitage is a place for silent reflection. There’s a bed, a wood stove, a camping stove for cooking, and a place set aside for prayer. Anyone in the community can come to the hermitage on their day off. Bill Clark is a striking figure. He’s a short wiry man with a shock of white hair that is even more noticeable because of his dark brown skin. He tells me that he finds the experience of working the land – and living in a community like this – a form of contemplation.”

The documentary painted a portrait of the kind of community the Ignatian Farm offered. Situated off Highway 6 just north of Guelph, this 600-acre working farm was on a parcel of land that also housed the college buildings where Jesuit priests once trained, including Bill Clarke. The classrooms long-gone, and instead of training for a vocation the members of the farm community worked the land. Except for the director and the chaplain, the 15 people who lived there were not Jesuits. Some were living with mental handicaps, some had severe physical problems, and some were volunteers who had come to share their skills. The farm was not a social work agency where professionals helped the helpless. This was a working farm where everyone worked side by side, a farm that ran almost like a religious community, where the ancient monastic tradition of “welcoming the stranger” was being played out in an unconventional and agricultural way. Those who came here learned to be productive and those who were open to the intense and tough demands of this way of life, stayed.

It was during my interview with Bill about his role as director that I learned about Byron – not the famous poet, but Byron Dunn the person Bill had lived with at the farm. Byron had been a violent, suicidal alcoholic who years before had shot half of his face off in a botched suicide attempt. For twelve years Bill and Byron shared the same room, until Byron died of cancer. That story made only a brief appearance in the documentary.

Trained as a civil engineer, Bill Clarke gave up that line of work when he joined the Jesuits almost six decades ago. He told me he had always wanted to experience what it was like to live in a community and to live as simply as possible. It was on this farm, he said, that he was able to meet the challenge of the Jesuit training he received there all those years ago: to be able to see God in all things. And especially in those who are vulnerable, damaged, outcast.

Byron’s story stayed with me long after that radio documentary was filed in the CBC archives. When I was reporting for The Catholic Register I covered a presentation by Bill at a conference. In our interview he told me more about Byron and I remember saying, “There’s a book in this, you know.” The farm project had been terminated by then, a difficult and divisive decision all round. But Bill’s farm community experiences and Byron’s remarkable story would certainly cast a long shadow on anything he might write. There were silences during our conversation. I remember a phrase I used in the CBC documentary that Bill was “not at ease with personal conversation.” His is a soft-spoken approach – always a challenge for someone with a recording device. But he listened intently and waited before offering a thoughtful opinion or reply and that’s always a gift for a documentary maker and an editor-in-waiting.

During our conference conversation/interview – which I recorded because he was “on the record” – Bill more or less outlined the book that he would go on to write and that I would eventually edit. Byron was at the centre. “I was just as wounded as he was, but I had good ways of covering it up,” Bill told me back then. “I could hide my wounds quite easily, while people with a mental handicap, they don’t hide their wounds. It’s pretty obvious. But, you know, in some ways it’s not that obvious because the wound is not that they have a mental handicap. The wound is that they have been rejected and they don’t have a place. There’s a deep wound towards their self-worth and their value. But I think in our community, or even in L’Arche, we just talk about people whose wounds are more obvious and who teach us not to be afraid of our own wounds. They have incredible gifts of fidelity, simplicity and tenderness and they call me to fidelity.”

During our conference conversation/interview – which I recorded because he was “on the record” – Bill more or less outlined the book that he would go on to write and that I would eventually edit. Byron was at the centre. “I was just as wounded as he was, but I had good ways of covering it up,” Bill told me back then. “I could hide my wounds quite easily, while people with a mental handicap, they don’t hide their wounds. It’s pretty obvious. But, you know, in some ways it’s not that obvious because the wound is not that they have a mental handicap. The wound is that they have been rejected and they don’t have a place. There’s a deep wound towards their self-worth and their value. But I think in our community, or even in L’Arche, we just talk about people whose wounds are more obvious and who teach us not to be afraid of our own wounds. They have incredible gifts of fidelity, simplicity and tenderness and they call me to fidelity.”

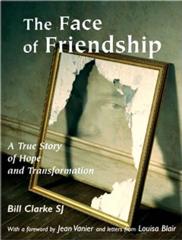

A couple of years later and when I was commissioning editor at Novalis, Bill completed that book. The Face of Friendship – A True Story of Hope and Transformation, with an introduction by Jean Vanier, was published in 2004 by Novalis who recently reprinted and re-packaged the book.