There was nothing special about it. It was blue, a very typical box containing a stack of sheets of 8 ½ x 11paper. When I opened it I observed that these were not the usual ‘print-outs’ from a desktop printer, but a set of photocopied pages. The lines were varied in the intensity of the print because these were indeed typewritten pages, not the result of word-processing software. I was intrigued. In the age of digital files here was a manuscript that had been typed, corrected manually, rather than electronically keyboarded. It was ‘old school’ and I was already captivated.

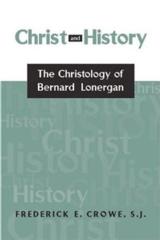

I checked the author’s name on the title page, Frederick Crowe SJ, and I began flipping through my mental contacts lists to try and recall how I knew that name. I knew I knew it, but at the time I couldn’t remember how or why I remembered it. The subtitle on the title page helped as it referenced the name Bernard Lonergan SJ. Suddenly I realised that I had something quite extraordinary in my hands. The pages in this blue box comprised what was to be Frederick Crowe’s final published book: Christ and History: The Christology of Bernard Lonergan from 1935 to 1982.

I checked the author’s name on the title page, Frederick Crowe SJ, and I began flipping through my mental contacts lists to try and recall how I knew that name. I knew I knew it, but at the time I couldn’t remember how or why I remembered it. The subtitle on the title page helped as it referenced the name Bernard Lonergan SJ. Suddenly I realised that I had something quite extraordinary in my hands. The pages in this blue box comprised what was to be Frederick Crowe’s final published book: Christ and History: The Christology of Bernard Lonergan from 1935 to 1982.

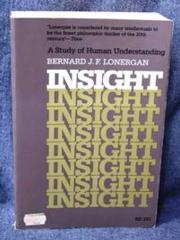

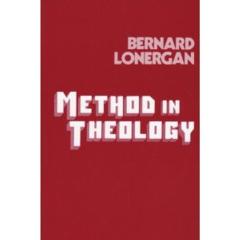

In these pages Frederick Crowe sought to address some of the gaps in the work of his former teacher and mentor, the great Jesuit philosopher and theologian, Bernard Lonergan, who died in 1984, leaving a wealth of published and unpublished materials behind him. Lonergan’s reputation is built on two foundational works: Insight: A Study of Human Understanding (1957) and Method in Theology (1972). Ever since their publication, scholars, and especially Frederick Crowe, have attempted to complete some of the “unfinished business” of Lonergan’s multifaceted inquiries into knowing and believing, history and economics.

In 1985, Frederick Crowe became the founding director of the Lonergan Research Institute, which he guided until 1992. With fellow Jesuit, Robert Doran and a large team of associate editors he took on the task of editing and preparing a 20+ volume series of the entire output of books and articles, everything ever written by Bernard Lonergan – a research and publishing project that continues to this day.

I remember feeling nervous with that blue box in my possession. Up to that moment in my editing career I had spent a great deal of time with first-time and relatively inexperienced authors. Here in my hands was the work of a major scholar with a highly acclaimed body of work behind him, much of it invaluable to those theologians and philosophers around the world with an interest in the work of Bernard Lonergan.

With major publishing initiative such as this, I moved from my usual desk to my editing chair (a secret corner on the second floor of the library at Saint Paul University) and began

to read each page with the same care I tried to give every manuscript I reviewed. Typically, I work with a pencil in one hand and a pad of yellow sticky notes in the other. With the pencil I try to keep track of the tedious but important things: punctuation, spelling, verb tenses, word usage, writing “tics”, grammar challenges, and also page-layout issues. The yellow notes are there to help me keep track of content issues: focus, subject matter, argument, gaps, inconsistencies, missing explanations, repetitions, and the like. By the time I finish with a manuscript there are usually multiple yellow notes on each page and copious pencil notes in the margins. I remember the first page escaped untouched by both pencil and yellow note, then the next, and the next… And on it went. This manuscript was different and quite unlike anything I had seen before and, indeed, unlike anything I have seen since.

to read each page with the same care I tried to give every manuscript I reviewed. Typically, I work with a pencil in one hand and a pad of yellow sticky notes in the other. With the pencil I try to keep track of the tedious but important things: punctuation, spelling, verb tenses, word usage, writing “tics”, grammar challenges, and also page-layout issues. The yellow notes are there to help me keep track of content issues: focus, subject matter, argument, gaps, inconsistencies, missing explanations, repetitions, and the like. By the time I finish with a manuscript there are usually multiple yellow notes on each page and copious pencil notes in the margins. I remember the first page escaped untouched by both pencil and yellow note, then the next, and the next… And on it went. This manuscript was different and quite unlike anything I had seen before and, indeed, unlike anything I have seen since.

As I recall, I think I made a handful of technical edits. I shortened a sentence here and there and I don’t remember having to remove a single repetitious paragraph or to ask for a content-gap to be filled. This book was a thoughtful and generous interpretation and explanation of the ideas of one of Frederick Crowe’s colleagues, his former teacher, his mentor, and his fellow Jesuit. It was a work carried out with the utmost respect for the individual and for his intellectual rigour.

As I recall, I think I made a handful of technical edits. I shortened a sentence here and there and I don’t remember having to remove a single repetitious paragraph or to ask for a content-gap to be filled. This book was a thoughtful and generous interpretation and explanation of the ideas of one of Frederick Crowe’s colleagues, his former teacher, his mentor, and his fellow Jesuit. It was a work carried out with the utmost respect for the individual and for his intellectual rigour.

After a few days working on the contents of the blue box, I received a phone call from someone connected to the Lonergan project explaining that “it would be really good if this book could come out around the time of Father Crowe’s imminent 90th birthday,” which, God-willing, he would celebrate in 2005.

Now one of the challenges of working with any manuscript is for an editor to recognize the important distinction between the art of producing quality and engaging material by the writer and the important craft-based skills of the editor: honing, shaping, turning, trimming, joining, polishing, much in the same way that a carpenter works with wood. These are skills born of the experience and deep appreciation of a craft and pleasure in working with quality materials.Crowe and Lonergan are experts in the subtle nuanced theological and philosophical arguments of scholarly precision. They have worked with both acolytes and experts immersed in the complexities of their subject matter. It was important for me, an editor and not a Lonergan expert, to not let myself become distracted by this elevated intellectual content and to focus on the typical and technical requirements of a manuscript. As an editor, it’s important not to assume an expertise that you do not possess. After all, Frederick Crowe had been ably edited over the years by his scholarly content editor, academic colleague, and fellow Jesuit, Gordon Rixon.

As the (then) commissioning editor of a commercial publishing house my task was to avoid getting caught up in what I didn’t know about Lonergan’s precise analytical, technical, philosophical, and theological approaches. My role was to stick to the craft of the editor: Is this clear? Is it elegant? Will a non-expert reader picking up this work for the first time find a way into the riches inside this book? And perhaps the simplest, though most important editing task of all, are these pages all in the right order?!

As the (then) commissioning editor of a commercial publishing house my task was to avoid getting caught up in what I didn’t know about Lonergan’s precise analytical, technical, philosophical, and theological approaches. My role was to stick to the craft of the editor: Is this clear? Is it elegant? Will a non-expert reader picking up this work for the first time find a way into the riches inside this book? And perhaps the simplest, though most important editing task of all, are these pages all in the right order?!

I never met Frederick Crowe, though we did speak on the phone a few times in the few months between receiving this manuscript in a blue box and the eventual publication of the work. I would not use the word “chat” or “conversation” to describe these brief formal exchanges. His focus was on the details of the book and he approached it with a steel-trap memory for detail that was astounding. The resulting publication, Christ in History – The Christology of Bernard Lonergan, was published by Novalis in 2005, the year that Frederick Crowe celebrated his 90th birthday.

Frederick Crowe died in April 2012 at the age of 96 and after 76 years as a Jesuit. At the funeral, his colleague, Robert Doran suggested that “perhaps Fred’s principal legacy to many of us, even beyond the fact that we owe to him the preservation of Lonergan’s legacy – and we would not have that legacy were it not for Fred – is the orientation that he took to the future, the conviction that he embodied regarding how we, and especially the church, are to move into that future. As he grew older, his mind and his interests literally grew younger, more in touch with the new things that God is doing in our world.”

Frederick Crowe’s typed pages in a blue box became his final published book which has since become a standard work about the theology and philosophy of that other great Canadian Jesuit, Bernard Lonergan,

***************************************************************************

Two quotes from the works of Bernard Lonergan, SJ

In the ideal detective story the reader is given all the clues yet fails to spot to criminal. He may advert to each clue as it arises. He needs no further clues to solve the mystery. Yet he can remain in the dark for the simple reason that reaching the solution is not the mere apprehension of any clue, not the mere memory of all, but a quite distinct activity of organizing intelligence that places the full set of clues in a unique explanatory perspective.

By insight, then, is meant not any act of attention or advertence or memory, but the supervising act of understanding.

From: Insight: A Study of Human Understanding (1957) by Bernard Lonrgan, SJ

********************************************************************

So faith is linked with human progress and it has to meet the challenge of human decline. For faith and progress have a common root in man's cognitional and moral self-transcendence. To promote either is to promote the other indirectly. Faith places human efforts in a friendly universe; it reveals an ultimate significance in human achievement; it strengthens new undertakings with confidence.

From: Method in Theology (1972) by Bernard Lonergan, SJ.