Ten years ago, a brain tumour left me severely deaf. Over the years the deafness deteriorated to the point that I was a candidate for a cochlear implant. For an adult whose hearing was perfect until the age of 45, there was no hesitation in my mind about returning to the world of the hearing. I went through with the surgery.

T hrough the process of getting the implant, and in the years since, I have realized that there are serious ethical issues for those who were born into the deaf culture. Cochlear implants are a hot button issue for that culture. Do deaf parents of a deaf child have her “cured” with cochlear implants so that she can join the world of the hearing? Or, do they welcome a deaf child into the thriving subculture of the deaf community?

hrough the process of getting the implant, and in the years since, I have realized that there are serious ethical issues for those who were born into the deaf culture. Cochlear implants are a hot button issue for that culture. Do deaf parents of a deaf child have her “cured” with cochlear implants so that she can join the world of the hearing? Or, do they welcome a deaf child into the thriving subculture of the deaf community?

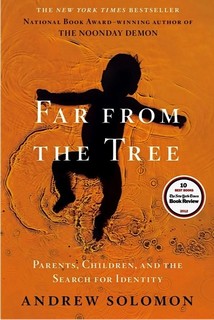

Thus, it was with great interest that I read Andrew Solomon’s work, Far From the Tree – Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity (Scribner, 2012). Solomon’s explorations began many years ago, with his attempt to understand his own identity as a gay male and his eventual discovery that his experience of belonging to a subculture wasn’t that different from the experience of people who are part of the deaf culture and dwarf culture.

One deaf person describes deaf culture as “a minority group with our own language, culture, and heritage.” Once Solomon found that his identity had similarities with the identities of the deaf and dwarf communities, he wondered, “Who else was out there waiting to join our gladsome throng.”

Solomon distinguishes between vertical and horizontal identity. Vertical identity is shared across the generations. I am Caucasian because my parents were. I speak English because my parents did. I have blue eyes and grey hair because I inherited these traits from my parents.

Horizontal identity is often seen as a flaw. A man and woman do not set out to give birth to a child with Down Syndrome. Horizontal identity deals with areas where I am foreign to my parents and I need to acquire my identity from a peer group. It is by observing and being immersed in a subculture outside the family that I learn my identity.

After dealing with the deaf and dwarf cultures, he explores the world of Down Syndrome, autism, schizophrenia, severely disabled children, parents of children who turn to crime, and several other disabilities.

Solomon describes these children as having fallen far from the tree – “apples that have fallen elsewhere – some a couple of orchards away, some on the other side of the world.”

There is a profound difference between parents and the child. An exceptional identity can be isolating “unless we resolve it into horizontal solidarity.” Examples of this solidarity can be the sense of community that takes place in the deaf subculture, among those with dwarfism, and among those with Down Syndrome.

Solomon says that if the physical or psychic place to which you were born cannot understand you, “An infinitude of locales beckons. If you can figure out who you are, you can find other people who are the same.”

He states, “many of the worlds I visited were animated by such a fierce sense of community that I experienced pangs of jealousy.”

He often refers to the messy ethical questions that can surface. Would the world be a better off place with fewer disabled children being born? Does genetic screening lead to eugenics? What would the world look like with disability being eliminated?

A strong theme in Solomon is that of cure from disability versus acceptance of disability. He says that we need to find ways of alleviating the disability while respecting and valuing the difference.

A strong theme in Solomon is that of cure from disability versus acceptance of disability. He says that we need to find ways of alleviating the disability while respecting and valuing the difference.

I was disappointed that Solomon never mentioned the work of Jean Vanier and his worldwide network of L’Arche communities for the handicapped. L’Arche communities are a perfect example of Solomon’s basic insight that close contact with disabled people will make the world more human.

He paints a very hopeful picture and comes down on the side of acceptance of the disability. He praises the diversity in the world and concludes “differences unite us.” L’Arche has shown us how a child with multiple severe disabilities can move so many people. One father described for Solomon how his severely handicapped son is “pure being … in a totally unconscious way, he is what human is.” L’Arche communities give daily testimonies such as that.

This is a heavy book and it involves a serious investment of time and energy. It is, after all, over 960 pages.

Solomon’s style is readable and engaging, partly because he relies primarily on extensive interviews with over 300 families. The manner with which he interacts with them, almost embedding himself into their lives, is impressive.

On the surface, this could be a depressing book, unless you like reading about difficult lives. But, there is a strong element of hope in it. It never ventures into depression or hopelessness. It is a celebration of the parental bond that proves so strong and so healing.

This is essential reading for anyone who has ever felt different or other, or for parents who have struggled with raising a child who has fallen far from the family tree.

Far from the Tree has been described as groundbreaking. That is because, although work has been completed on understanding each issue in the book, there is “nothing addressing this overarching issue of illness and identity.”

Parenting challenged the parents in this book, but almost none of them regretted it. Some parents become extraordinary in how they care for their exceptional child in amazing ways.

Solomon suggests that in addition to nature and nurture, there is also an “unknowable inflection of spirit or divinity.” What he means is that our children are the children that we had to have, and at the time we had them. That is what allows parents of disabled children to be inclined toward the light and to remain so hopeful.

Those of us with faith would speak of the parents having received from God the grace to deal with what life has offered them. Most of the families described in the book have ended up grateful for experiences they would have done anything to avoid.

I can relate. I would never have chosen a path that included a brain tumour and deafness, but it’s been the most important experience in my life for teaching me how to be a priest and I’ll always be grateful for my experience.

One parent says, “I have increased compassion for others due to my experience.” The mother of a child with Down Syndrome says that to talk about a cure for Down Syndrome is to diminish the value of people with the intellectual disability. “These experiences have made us who we are as parents.”

One of the most moving parts of the book is his account of getting to know the parents of Dylan Klebold, one of the perpetrators of the 1999 massacre at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado.

Sue Klebold offers perhaps as good as anyone a summary of a lengthy book about people with disabilities and the power of the enduring love of their families when she speaks of her son’s actions:

“Columbine made me feel more connected to mankind than anything else possibly could have. I accept my own pain; life is full of suffering, and this is mine. I know it would have been better for the world if Dylan had never been born. But I believe it would not have been better for me.”

That connection to humanity is what Solomon hopes for. He ends his book by offering his view on what happened to him in the process of researching the book.

“Sometimes, I had thought the heroic parents in this book were fools, enslaving themselves to a life’s journey with their alien children, trying to breed identity out of misery. I was startled to learn that my research had built me a plank, and that I was ready to join them on their ship.”