Francis J. Devine, S.J., was rotund, very rotund in fact, a kind of chestertonian figure, and in many ways every bit as witty. He was nearly as tall as G. K. Chesterton, who was just shy of 2 metres, and Devine weighed every bit as much, in the neighbourhood of 130 kg.

He loved to poke fun at himself and at his ungainly figure with its noticeable protruding midriff very reminiscent of Chesterton. Devine spoke frequently of it as if it were not an extension of himself, but rather as something there having its own life and character.

Perhaps that was one reason why so many people found him so delightful.

Chesterton also viewed his extensive centre in somewhat the same way, and had no hesitation in taking a poke at himself. Once during the Great War a woman of some note in London society asked him, “Why are you not out at the front?” to which he quickly replied, “Madam, if you go round to the side, you will see that I am!”

To George Bernard Shaw, a man with a very sharp tongue and pen to go with it–but with nothing protruding, such was his bird-like figure–Chesterton once remarked that “to look at you, anyone would think a famine had struck England.” Never short of a quick response, Shaw countered to his friend, and “to look at you, anyone would think that you have caused it”!

Certainly, it was hard not to appreciate Devine in a similar way, especially his sense of humour, and his willingness to tell stories about himself, some connected with his weight, others about his own follies and mishaps.

He was forever insisting that he was on a diet. Yet, he was often caught out snacking on all the things that made him fat in the first place. Chocolates and marshmallows he especially favoured, and although whenever offered to sample some, he would reject them out of hand. He was on a diet.

Later, however, he would make up for his moment of courageous abstinence by helping himself to whatever remained of the box in the Jesuits’ recreation room.

Later in his life, when all pretenses of dieting had long since disappeared, he was told that certain breakfast cereals were notable for their fat-reducing qualities.

Shredded wheat, he learned was especially helpful for weight-loss. He took up eating that cereal with a seriousness that defied all imagination. Before long he was consuming several bowls of it each day which, were it to have any weight-loss value, quickly came to naught.

He smothered each bowl in two-percent milk with heaping teaspoons of sugar or, for good measure, maple syrup. Maple sugar, he insisted, was a “natural” sugar, so therefore was not fattening!

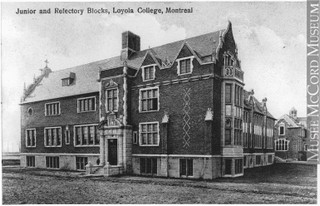

One incident Devine delighted in recounting about himself happened during the early 1940s when he had been appointed to Loyola College in Montreal to become a professor of French language and literature. Young and recently ordained, he happened to be standing one morning in front of the college.

Ever eager to practice his French whenever possible–he had shortly before completed his Master of Arts degree in French literature–and to use his new priestly faculties whenever necessary, as he stood taking his after-breakfast smoke, he noticed a large crowd gathering in front of Loyola on Sherbrooke Street around what, he thought, was someone in great distress.

When he heard someone shout to another bystander, “Il est mort! Il est mort!” he rushed over explaining loudly to one and all, “Je suis un prêtre”, and quickly moved his already extensive self to the front of the crowd.

When he heard someone shout to another bystander, “Il est mort! Il est mort!” he rushed over explaining loudly to one and all, “Je suis un prêtre”, and quickly moved his already extensive self to the front of the crowd.

There to his surprise, he saw stretched out on the pavement, a dead horse. This was still the era of horse-drawn milk-carts in Montreal.

From 1942 until 1958, Devine became known as one of Loyola’s best teachers of French. Long before French would become by Quebec’s law a necessity for English-speaking students, Devine recognized the value for them of the language and of its tremendous body of literature.

He wanted nothing more than that they gain confidence in their daily use of it. To that end, he developed a stash of pedagogical methods for assisting them. One such was to assign sections from a morning French-language newspaper so that they would come to speak in French about the day’s events in front of the class.

He excelled, too, as director of French-language dramatic presentations by his class or in company with other classes, and strove to make sure that those performances were of the highest dramatic quality. His own great admiration and fluency in French, and his never-failing encouragement and good humour, were infectious, and these went a long way in encouraging student to use French as often as possible.

Of course, he did everything, inside or outside the classroom, with wit, self-put-downs, wry humour, and an engaging humility which students came to admire greatly.

For a generation at Loyola, Devine had come to be known as the amusing but hefty Jesuit with a healthy sense of the absurd who loved nothing better than to be with students, to listen to them, teach them, and offer solutions to their problems, while all the time dispensing with a smile good doses of his common sense. When he left Loyola in 1958 to take up teaching French at Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, he was greatly missed