I have learned that one can find God in all things: this truism applies well to Japanese anime. In this entry, I would like to explore the use of the Christ-figure in anime. What is anime? Well, after WWII, Japanese culture was highly influenced by American culture. In the 1960s, Japanese artists adapted and simplified the “Disney” style animations they saw at the movies and used them to tell Japanese stories.

I have learned that one can find God in all things: this truism applies well to Japanese anime. In this entry, I would like to explore the use of the Christ-figure in anime. What is anime? Well, after WWII, Japanese culture was highly influenced by American culture. In the 1960s, Japanese artists adapted and simplified the “Disney” style animations they saw at the movies and used them to tell Japanese stories.

In the 1980s, the popularity of manga, the comic-book form, skyrocketed and the process of animating manga series as TV shows became big business; making titles like Dragon Ball Z familiar to westerners. Anime is known for its distinctive artistic style, its use of cartoons to convey serious literary themes, and frequent appeals to the zany, the magical, or the metaphysical.

T he first, obvious place to find Christian imagery in anime is the use of symbols and imagery. Images of the cross, mana from heaven, resurrections, etc are commonplace. Good characters may be drawn with halos or angel-wings; evil characters with names like “Kururo Lucifer” or “Gamora”. Japanese authors may uses these symbols loosely, or they may be interested in using them to more deeply explore aspects of the story and of human nature.

he first, obvious place to find Christian imagery in anime is the use of symbols and imagery. Images of the cross, mana from heaven, resurrections, etc are commonplace. Good characters may be drawn with halos or angel-wings; evil characters with names like “Kururo Lucifer” or “Gamora”. Japanese authors may uses these symbols loosely, or they may be interested in using them to more deeply explore aspects of the story and of human nature.

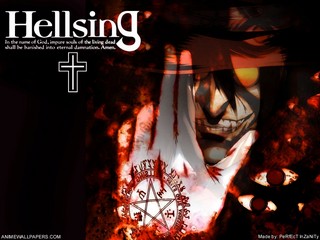

Professed Christians are rare, though not unheard of, in Japan, and so they are rare in anime. Such characters are almost never protagonists. They are usually a bit inaccurate, mythological, or exaggerated. Christian characters can represent cultural outsiders. A good example of this is Fr. Anderson from the anime Hellsing. Anderson is a priest secretly employed by the Vatican to hunt vampires. Awesome enough to be the hero of his own show! But he is not. He is actually an antagonist, because the hero of the story is a Vampire who helps humans. Anderson represents an uncomprehending foreigner: while he has ideals and honour, these very traits lead him into conflict with the protagonist. In Hellsing, Christianity is used to explore the story. But in other shows, the story can be used to explore Christianity.

The most interesting Christian themes in anime center around characters who are not Christians themselves but who represent Christ in the story. Most heroes can be considered Christ-figures because of the way in which they resolve the story through their actions. But some anime creators make more direct use of the Christ-figure to tell a story not just of resolution, but of redemption.

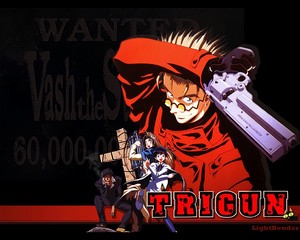

In my opinion, the most well-used Christ figure in anime is from the 1998 series Trigun. Trigun is primarily a western; as such it seeks out to explore the themes and archetypes of the great cowboy movies of the past few decades. The show's exploration of a western gunslinger as a Christ-figure is very deliberate. The hero's name is Vash the Stampede. While the character is an extremely skilled gunman, he has taken a vow never to kill. In a world where outlaws threaten innocent lives, Vash struggles to save the lives not only of the innocent but of thieves and murderers. Vash works to redeem and change the minds of criminals and “sinners”.

At one point in the series, Vash is depicted as a young man watching a spider catch a butterfly. He wants to set the butterfly free. An older character kills the spider, explaining that without food, a spider cannot survive. The older character states that the human mission is to save that which is beautiful from that which is evil … but the young Vash weeps and pleads that there must be a way to save both. His character rejects the logic of death and survival and seeks another way.

The author uses the story of Vash and the old west as a metaphor for the problem of human suffering. The people of the old west and of Jesus' time were convinced that the solution to suffering is for God to punish and kill the evil and raise the innocent to paradise. But Christ defied this logic; instead of using violence Christ came to suffer, to lay down his own life and teach others to do the same. Vash himself suffers terribly as a result of his refusal to kill, enduring great injury while trying to save people who are trying to kill him.

All of these moments are replete with Christological imagery: Vash wears red (standing for blood and life), he wanders in the desert, he has a transfiguratio n in which he appears to be a heavenly figure, he bears symbolic wounds, and he has an intuitive grasp of what people need in order to turn from sin and abundance of life. The latter episodes reveal that Vash is old enough to have been present when the world was a green paradise, and that his motivation is to remedy the wrong that turned the world into a desert wasteland: to give humanity have a new future.

n in which he appears to be a heavenly figure, he bears symbolic wounds, and he has an intuitive grasp of what people need in order to turn from sin and abundance of life. The latter episodes reveal that Vash is old enough to have been present when the world was a green paradise, and that his motivation is to remedy the wrong that turned the world into a desert wasteland: to give humanity have a new future.

The Christological themes are central but not isolated. The story integrates ideas from Buddhism and the samurai code. This makes for a rich and fruitful context in which eastern and western ideas can play off of one another. A good drama will always explore the human condition. And Trigun makes use of Christianity to deepen this exploration.

Anime can be very strange. Like any art form, it can be used to convey either fatuous, destructive themes or deeply human and redemptive ones. It is our role as discerning viewers to seek out that which is most good and benefit from it. It is not my desire to bring Christ to these stories. It is my belief that, implicitly or explicitly, Christ is already present in the human story.

The Jesuit missionaries who first came to Japan were deeply moved by the culture and the people they encountered. They found Christ already at work in Japan. Their faith lead them to openness and receptivity. Our faith must lead us to the same; only then can we truly find God in all things.

Reprinted with permission from Ibo et non Redibo.