Frank Capra’s beloved classic It’s a Wonderful Life explores a number of themes, but perhaps the final word was left to the angel Clarence, who leaves his copy of Tom Sawyer to the redeemed protagonist George Bailey with these words inscribed: “Remember George, no man is a failure who has frien ds.”

ds.”

This declaration, that even the most mundane and provincial of lives can be considered a success if one has the gift of friendship, is profoundly Christian. Yet it also immediately begs a number of questions. What is true friendship? What differentiates friendship from other kinds of loving relationships? Is the number or the quality of friendships more important in life?

The nature of Friendship has been a topic of study from time immemorial. Many of the ancient Greek philosophers discuss it. For example, Aristotle wrote that “The excellent person is related to his friend in the same way as he is related to himself, since a friend is another self; and therefore, just as his own being is choice-worthy to him, the friend's being is choice-worthy for him in the same or a similar way.” The Greeks liked the idea that in friendship, two selves are like one person with two bodies, much closer to our image of marital union.

Various cultures also approach friendship differently. In many Islamic cultures, for example, friendship requires a deep commitment and expectation of mutual sacrifice for the other. Therefore, people tend to enter into them carefully. Germans and northern Europeans are very similar.

In America, however, the term friend has a much looser connation. Adults call almost every person they know, a “friend”. Exclusive friendships, even “best friends” tend to be frowned upon as leading to cliquishness. The high rate of mobility in America has also led to a decline in lasting friendships. And as social networking becomes the new forum of exchange, with “friend requests” being their entry point, it may be that our notion of friendship is arriving at new levels of superficiality and transience.

A study reported in the June 2006 issue of the American Sociological Review argued that Americans are suffering a loss in the quality and quantity of intimate friendships since at least 1985. The study writes that 25% of Americans have no close confidants and that the average number of confidants per person has dropped from four to two.

Even earlier, C.S. Lewis argued that in the West, modern friendships have lost their depth and importance. In The Four Loves he wrote: “To the Ancients, Friendship seemed the happiest and most fully human of all loves; the crown of life and the school of virtue. The modern world, in comparison, ignores it.”

Lewis describes four major kinds of love: Storge or affection, Philia or Friendship, Eros or romance, and agape or unconditional love. He calls Philia or friendship “the least biological, organic, instinctive, gregarious and necessary of our Loves”, since the species don’t need it to reproduce, but goes on to argue that it is the most profound of relationships precisely because it is freely chosen. Perhaps the first step for our culture, broadly speaking, is its recovery.

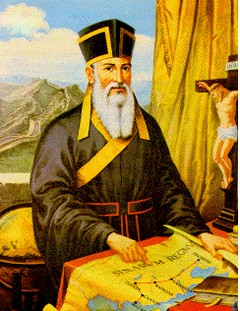

After screening Capra’s film to my cinema class, I found myself reading a book by the celebrated Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci called On Friendship: One Hundred Maxims for a Chinese Prince. Ricci’s scientific and philosophical abilities had led him to be accepted into Chinese kingdom, even invited to be an advisor to the  Emperor, the first Westerner to be invited into the Forbidden City. He mastered Mandarin, and wrote the first edition of On Friendship in 1595; it became best-seller in China, but was only translated into English in 2009.

Emperor, the first Westerner to be invited into the Forbidden City. He mastered Mandarin, and wrote the first edition of On Friendship in 1595; it became best-seller in China, but was only translated into English in 2009.

To be clear, Ricci is drawing primarily from classical European sources when he composed his sayings, but they were a great bridge between the two cultures. There is insight in these aphorisms, but like all such sayings they are more like spurs to ongoing reflection. Ricci will say in one breath something like the following, which appears to endorse quantity:

“If you see someone’s friends are like a forest, then you know that this is a person of flourishing virtue; if you see that someone’s friends are as sparse as morning stars, then you know that this is a person of shallow virtue.” (#61)

Then he will go on and say this, which appears to advocate for a certain reluctance to embrace the bonds of friendship:

“The honourable man makes friends with difficulty; the petty man makes friends with ease. What comes together with difficulty comes apart with difficulty; what comes together with ease comes apart with ease. (#62)

The truth about friendship, therefore, may lie in the centre. The number of people who turn out for a person’s funeral may be indicative of that person’s capacity for friendship. More than 100,000 people lined the streets in  Darjeeling at the funeral procession of a Jesuit of my province a few years ago, a much beloved priest who had toiled there many decades.

Darjeeling at the funeral procession of a Jesuit of my province a few years ago, a much beloved priest who had toiled there many decades.

But funeral numbers may also mean nothing (one thinks of that scene in Citizen Kane, in which all the other influential people come out for Kane’s funeral, despite his having isolated his soul from society). Moreover, as Christians we know that love is something that transcends such quantifications.

There are souls who live and love and die in obscurity, hidden saints in our midst, whose Philia may be lived at a much more vertical level, encompassing the breath of the body of Christ on earth and the communion of saints. They are perhaps the truly great lovers. These are people who you may only meet once, but who affect you in a profound way. Being recognized in this life or not is irrelevant to them. The number of friends they have is irrelevant to them. They do not calculate nor categorize their relationships. They simply have a capacity for love, which while being universal, is not any less personal. Perhaps we know one or two persons like th at.

at.

George Bailey, while “not a praying man”, may have nonetheless been a great man. This is not because he knew everyone in his town and called them friends. Capra’s film shows him to be a success as a human being because he had served the townspeople’s needs for many years, in both his weakness and strength, in good times and bad times. He didn’t know it, but he loved the people of his town. They, in their turn, loved him, and rally to his aid in time of financial crisis. Mutual giving may be the basis of true friendship, but we also see that it must have an absolute lack of expectation of return as its condition. True friendship, then, will show itself as the liberating and ennobling experience that it is meant to be.