After two months of winter, the landscape seems rather forlorn, lonely, dreary, on these cloudy days of which we seem to get more than our fair share in Ottawa. As I look out my window towards the houses of Old Ottawa South, it is hard to imagine that Ash Wednesday and Lent are upon us, and that Easter is only about two months off, with its promise of new life and growth in spirit and nature.

After two months of winter, the landscape seems rather forlorn, lonely, dreary, on these cloudy days of which we seem to get more than our fair share in Ottawa. As I look out my window towards the houses of Old Ottawa South, it is hard to imagine that Ash Wednesday and Lent are upon us, and that Easter is only about two months off, with its promise of new life and growth in spirit and nature.

In most places of the globe, these important days in our annual calendar usually anticipate Spring, even welcome it. Not so here, or at least it is very hard to think of Spring as we struggle through one of the coldest and snowiest winters Ottawa has had to bear for some years. It’s been taxing: blistering cold, followed by the longest January thaw in Ottawa’s history, then even colder days, while today we are getting pelting cold rain with ten degrees above.

Ottawans, though, seem to take winter in stride. They speak warmly, even enthusiastically, about skating on the longest skating rink in Canada, as they insist the Rideau Canal is, or about skiing on the many slopes of the local Gatineau Hills, or cross-country skiing around through the many parks which intertwine the city. I do neither of these sports, so I am pitied by many. “You don’t understand winter,” someone remarked to me recently, as if I had just arrived from some warm climate. He too seemed to pity me.

Nonetheless, Lent still seems to be arriving early. That isn’t really so, of course, for it often arrives in February. “Lent already?” someone said to me the other day. “Seems awfully early”, she went on as if we were still in early January. “I’ve still got some Christmas decorations up. Thank God it isn’t like it used to be, with old-fashioned Lent so hard and unforgiving.” Since she is even older than I am, she remembers the Lents long before the new fasting regulations of the late 1950s and early 1960s changed our Lents forever.

As we knew it then, old-fashioned Lent seemed like mandatory misery as a down payment on the soul’s future happiness. Attired in what memory seems to recall as grim trappings, Lent was a season of joylessness, of forty days with meatless Fridays and strict fasting and the ever-present resolution of whatever it was we “gave up” for the season.

Even as children we were well taught in the art of facing meatless days and fasting and “giving up”, and of surviving. “It’s good for you,” our mother used to remind us. Perhaps it was, but I scarcely thought so then, and have lingering doubts even now.

What I recall is endlessly waiting for Easter, which meant waiting for winter to end, more or less, since some Easters could be as snowy as Christmas. At least, however, we could get back eating normally like all our Protestant school-friends.

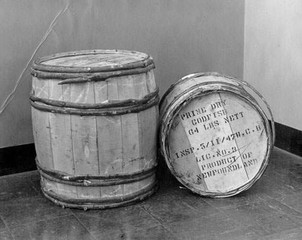

What I remember the most about Lent was the salted cod. Salted cod! Really awful stuff, giving off a smell that even sixty and more years later, I wince at the thought of ever having to eat it again.

Fortunately I don’t.

No matter how good our mothers were at cooking—and they were excellent cooks–no matter how they tried to camouflage the taste, it tasted like unappetising salted cod. Still, that was about the only fish sold in the stores.

Growing up in eastern Ontario, fresh fish was unavailable during the winters, and besides, salted cod could survive easily enough the lack of refrigeration common in those years. Sea food was unknown. Perhaps they knew about such things in Toronto, but we never went there.

Sardines were often an alternative Friday dish, of course. Pried out of small tins, they reeked of fish-oil, and looked dreadfully unappetising. If only we had had available the Italian sarde. Lent in Italy was every bit as severe, however more gentle the climate, but Italians had sardines, beautiful, large, fresh uncanned sardines.

Everywhere, they were and still are available in Italy. The poorest of the poor fish, for protein-needy Italians fasting in Lent, the lowly sardine was the answer. Sicilians love their bucatini con le sarde, Venetians their sweet and sour sarde in soar, others their sarde con peperonata, sarde alla lupa, sarde in agrodolce, and on and on.

Yet no one in our area knew anything about Italians except some vague prejudices arising from the war and the local “shoemaker” who was Italian, although no one knew why he ended up in a small, boring village in eastern Ontario.

Besides, on meatless days he ate like all the rest of us: salted cod and oily sardines out of little tins. It worked. Of course it did, and as one of my elderly uncles–or at least he seemed elderly to a ten year old–would have insisted: “We are the better for it”!

Well, all that changed in the 1960s. The Lenten fast and meatless days became greatly modified. Fasting became a voluntary commitment during Lent along with the meatless days, and both were reduced to two compulsory days only, Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.

We were encouraged to emphasize not the “giving up” of something for Lent, but rather to look to changing interiorly, to seeking the grace for a true conversion, for a genuine repentance of heart.

Indeed, Lent calls us to that, while it still encourages us to penance and fasting, of course, and to abstaining at times from what may hinder grace. All in all, a good balance.

Meantime, and before Ash Wednesday and Lent take over, roll on Shrove Tuesday. Bring out the pancakes lathered in sweet Canadian butter and smothered in lovely Canada No. 1 light maple syrup. Then afterwards resolve to be good!