A 2017 Lenten Bookshelf: A Second Look at a Six Fold Path: Part 4 – Dominican

By the solemn forty days of Lent the Church unites herself each year to the mystery of Jesus in the desert.

(From Article 540 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church)

In this six-part series, Kevin Burns selects a book for each week of Lent. Each book speaks to one of the great traditions within Catholic culture. Each book also shows how its author struggles to apply that tradition. Six different approaches to the same journey through the desert of Lent to the Easter promise of resurrection.

Week Four: Timothy Radcliffe O.P. and the challenges of the Dominican path.

St. Dominic (c.1170 – 1221) was a contemporary of St. Francis but unlike Francis, a time when monarchs sought to build Christendom through demolition and conquest (this was the era of Crusades and Cathar and other heresies after all). These two founders of religious orders looked to the power of prayer and preaching instead of violence and control. St. Dominic founded his community as the Order of Preachers, and based what evolved as Dominican practice on the simplicity of the Augustinian Rule, with precepts such as:

St. Dominic (c.1170 – 1221) was a contemporary of St. Francis but unlike Francis, a time when monarchs sought to build Christendom through demolition and conquest (this was the era of Crusades and Cathar and other heresies after all). These two founders of religious orders looked to the power of prayer and preaching instead of violence and control. St. Dominic founded his community as the Order of Preachers, and based what evolved as Dominican practice on the simplicity of the Augustinian Rule, with precepts such as:

“The main purpose for you having come together is to live harmoniously in your house, intent upon God in oneness of mind and heart…”

“Be assiduous in prayer…”

“Subdue the flesh …”

“You should either avoid quarrels altogether…”

And with the directive for all members of the order to pursue a communal way of life “not as slaves living under the law but as men living in freedom under grace.”

The Dominican way is built on the creation of communities of learning, each of which encourages its members to further their own studies, to teach with the greatest of skill, to preach effectively and convincingly, and to lead of life that is ordered by a disciplined approach to prayer. The Dominican image is one of erudition and in time its members became the Church’s systematic teaching wing.

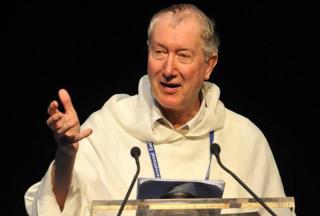

The British Dominican, Timothy Radcliffe, is a renowned scripture scholar and preacher based at Blackfriars, the Dominican college at Oxford University. In 1992, he was named “Master of the Order of Preachers” (effectively the order’s CEO), an office he held for nine years. Radcliffe published works that bridge the worlds of the academy and the institutional church, and which have found their way into the contemporary discourse on religion and society.

His books have a directness, some say bluntness, that captures and holds the reader’s attention: I Call You Friends in 2001; Seven Last Words in 2004; What is the Point of Being a Christian? in 2005; Why Go to Church? – The Drama of the Eucharist in 2008; and Take the Plunge – Living Baptism and Confirmation in 2011.

In 2015, Pope Francis named Radcliffe as a consultor to the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace to assist it in its role “to promote justice and peace in the world in accordance with the Gospel and the social teaching of the Church.” But Radcliffe’s inclusive theology has also made him a lightning rod for hostile allegations. To enter his name in an online search is to invite distress. But instead of doing that, why not read his own words instead?

As Master of the Order of Preachers, Radcliffe wrote annual letters to the worldwide Dominican membership. In his 1998 letter, The Promise of Life, he could also be addressing all seekers and searchers on a Lenten journey, hoping for a mystery, but still lost somewhere in between.

Firstly, Radcliffe reminds us that to be human is to experience frailty:

We are not angels. We are passionate beings, moved by the animal desires for food and copulation. This is the nature which the Word of life accepted when he embraced human nature. We can do no less. It is from here that the journey to holiness begins.

He reminds us how much we need the support of those around us:

We need brothers and sisters who are with us as our hearts are broken and made tender.

There is no “easy route” and though we may often feel lost, we are never alone:

Every wise person has always known that there is no way to life that does not take one through the wilderness. The journey from Egypt to the Promised Land passes through the desert. If we would be happy and truly alive, then we too must pass that way. We need communities which will accompany us on that journey.

He reminds us to endure darkness and absence:

The fundamental crisis of our society is perhaps that of meaning. The violence, corruption and drug addiction are symptoms of a deeper malady, which is the hunger for some meaning to our human existence. … God may lead us into that wilderness. There our old certainties will collapse, and the God whom we have known and loved will disappear. Then we may have to share the dark night of Gethsemane, when all seems absurd and senseless, and the Father appears to be absent. And yet it is only if we let ourselves be led there, where nothing makes any sense any more, that we may hear the word of grace which God offers; for our time.

A life of faith, as any Lenten journey, invites us to be bravely patient:

Our families have taught us to love; they may also have inflicted wounds on us that will take time to heal. To grow in this Christlike love takes time, and this time is given. It is a gift, and God always gives his gifts through time. He took centuries to form his people, preparing the way for the birth of his Son. God gives us life patiently, not in an instant.

Every encounter leads us into a much larger world:

The good shepherd who has come that we may have life and have it more abundantly, is the one who opens the gate, so that we may come out and find large open spaces. In prayer we make an exodus, beyond the tiny shell of our self-obsession. We enter the larger world of God. Prayer is a “discipline that stops me taking myself for granted as the fixed centre of a little universe, and allows me to find and lose and re-find myself constantly in the interweaving patterns of a world I did not make and do not control.” (quoting the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, Open to Judgement – Sermons and Addresses, 1994.)

The full text of all the letters from the various Masters can be found at the official Canadian Dominican website.

Last year, Timothy Radcliffe OP began treatment following a diagnosis of cancer of the mouth. He talks about this experience on The Art of Dying Well, a web-based initiative by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales. There he expresses his “trust in God and acceptance of whatever the future holds.” He adds that he believes we get a glimpse of eternal life when we enjoy life to the full.

The Art of Dying Well website is HERE Click on the section "Talking about death" to find Fr. Radcliffe's comments, as well as those of several contributors."

Next Week:

Edith Stein O.C.D. (St. Benedicta of the Cross) on the pursuit of a perfect coherence of meaning and the Carmelite path.

“…from God’s point of view – nothing is accidental … my entire life, even in the most minute details, was pre-designed in the plans of divine providence and is thus for the all-seeing eye of God a perfect coherence of meaning. Once I began to realize this, my heart rejoices in anticipation of the light of glory in whose sheen this coherence of meaning will be fully unveiled to me.”

No Comments