A Man for All Seasons

“I do none harm, I say none harm, I think none harm. And if this be not enough to keep a man alive, in good faith I long not to live.”

– St. Thomas More

The story of Thomas More has captured the imagination of Christians and non-Christians alike for hundreds of years. There are several Thomas Mores that attract attention. There is More the honest lawyer, friend of the king, eventual Chancellor of England, the one who would not take the oath of supremacy. There is More the humanist scholar, the philosopher, author of Utopia, Renaissance man and friend of Erasmus. And there is More the father, husband, and friend of all, the lover of God –More the saint.

The 1966 film by Fred Zimmerman is based on the 1960 stage play by Robert Bolt (The Mission), who also wrote the screenplay. It portrays the first and the third More, the legal scholar and the saint, and places its emphasis on the sacredness of “conscience”. The conflict in this telling is less concerned about who is the rightful head of the Church in England, but about why someone might be willing to die for his conscience on the question.

The 1966 film by Fred Zimmerman is based on the 1960 stage play by Robert Bolt (The Mission), who also wrote the screenplay. It portrays the first and the third More, the legal scholar and the saint, and places its emphasis on the sacredness of “conscience”. The conflict in this telling is less concerned about who is the rightful head of the Church in England, but about why someone might be willing to die for his conscience on the question.

The story pivots on Henry’s determination to divorce his wife Catherine to marry Anne Boleyn, the first of many wives, and the Church’s refusal grant him the annulment he desires. At first Thomas does not declare his own position on the matter, but when Henry declares himself the head of the Church in England, and requires the leaders in the land to swear to it, Thomas finds himself a more precarious situation. Henry respects Thomas, and what is more, knows that the people respect him. He wants Thomas more than anyone to “come over to his side”, subtly and not-so-subtly pushing him to take a public position.

One of the great exchanges takes place between More and his good friend the Duke of Norfolk (Nigel Davenport), who is concerned for his friend’s safety and can’t understand why he can’t join the rest of the English establishment in taking the oath:

The Duke of Norfolk: Oh confound all this. I’m not a scholar. I don’t know whether the marriage was lawful or not, but dammit, Thomas look at these names! Why can’t you do as I did, and come with us, for fellowship!

Sir Thomas More: And when we die, and you are sent to heave for doing your conscience, and I am sent to hell for not doing mine, will you come with me, for fellowship?

Thomas had a strong sense of justice, not only of legal justice – the laws that happen to be the laws of the land – but of the higher law, of divine justice. He was keenly aware that human laws must proceed from God’s law, or else they are flimsy grounds upon which to stake one’s soul. In many countries today, we have largely lost the sense that human laws are based on a divine fundament. Instead, we construe our laws to the common denominator of public will or support. In a sense, every citizen is his or her own Henry, unmoored (not pun intended) from this sense of higher law, and adhering, consciously or not, to a shifting sands doctrine of utilitarian ethics.

Thomas had a strong sense of justice, not only of legal justice – the laws that happen to be the laws of the land – but of the higher law, of divine justice. He was keenly aware that human laws must proceed from God’s law, or else they are flimsy grounds upon which to stake one’s soul. In many countries today, we have largely lost the sense that human laws are based on a divine fundament. Instead, we construe our laws to the common denominator of public will or support. In a sense, every citizen is his or her own Henry, unmoored (not pun intended) from this sense of higher law, and adhering, consciously or not, to a shifting sands doctrine of utilitarian ethics.

Thomas More arises as a giant figure in direct contrast to this kind of thinking. That he is willing to risk the ultimate punishment, and despite overwhelming pressure from his class, seems impossibly counter-cultural to us today, even folly. But there is something timelessly winsome about his stance, with its firm but gentle countenance, and because, as he tells his daughter Meg, it is ultimately a matter of love.

The film follows More’s domestic life, with strong performances by his wife Alice (Wendy Hiller), his daughter Margaret (Susannah York), and his headstrong and idealistic son-law-law Will Roper (Corin Redgrave). There is also the memorable role of Richard Rich (John Hurt), an ambitious young man who first solicits More’s help in getting a position at court. We have the unforgettable lines addressed to him by More, learning of his questionable patronage appointment: “Why Richard, it profits a man nothing to give his soul for whole world. But for Wales?”

Richard Rich is more tragic than villainous. The latter quality falls to the more sinister and political Cardinal Wolsey, played by a Jabba-the-Hut-like Orson Welles (Citizen Kane), and More’s primary nemesis, the treacherous and conniving Thomas Cromwell, played by Leo McKern. Cromwell is hell-bent on convicting More, with more than just the king’s weight bearing upon him as his motive. Between the two Thomases there is a battle of wits and a battle of grace.

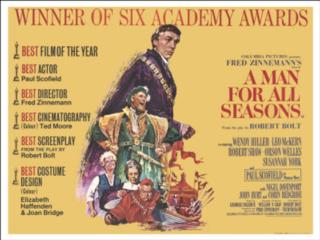

A Man for All Seasons, beloved by many viewers across the decades, won six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, in 1967. It also won best director, best actor in a leading role (Paul Scofield), best screenplay, best cinematography, and best costume design. Although play-like, it has held up over time; this year is the film’s 50th anniversary. More’s feast day in Roman Calendar is June 22.

A Man for All Seasons, beloved by many viewers across the decades, won six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, in 1967. It also won best director, best actor in a leading role (Paul Scofield), best screenplay, best cinematography, and best costume design. Although play-like, it has held up over time; this year is the film’s 50th anniversary. More’s feast day in Roman Calendar is June 22.

The screening of “A Man for All Seasons” takes place at Regis College, Toronto this Wednesday, Oct 12, at 7pm. Hand-out reflections and a short optional discussion to follow. The series of film screenings, curated by John D. O’Brien, S.J., runs Wednesday evenings until October 26. Dedicated to the Year of Mercy, these films develop the theme “justice and mercy shall embrace”. For details, see Regis College Film Series.

No Comments